Introduction

Crafting problems for legal writing instruction poses one of the most formidable challenges that legal writing professors face.[1] The problem in a legal writing classroom is an integrated learning experience,[2] the equivalent of a separate text, that professors must prepare each year to facilitate student learning. In the legal writing and communications discipline, professors annually, or even semi-annually, consider whether to re-use a problem,[3] create a problem from scratch, or borrow a problem from somewhere else. Yet, little scholarship exists to guide professors on how to create problems or adapt existing problems for new uses—while some articles identify some features of “good” problems, few guide novice professors on how to design one.[4]

The few articles that focus on problems provide general or anecdotal advice, but none specify why the recommendations are or should be best practices.[5] As a result, the field as a whole lacks shared nomenclature,[6] or jargon,[7] to accurately describe what it is that makes a problem “good.” No manual or guide exists to explain to novice professors how to design or redesign a problem, even given the wide range and variety of legal writing texts.[8] Because problem design is fundamental to teaching legal writing, the discipline should develop resources on how to do it.

Additionally, the fact that no shared nomenclature exists makes it challenging to articulate specific goals and outcomes as they relate to a given problem. For example, it is not uncommon to see a request on the legal writing professors’ listserv asking if someone is willing to share a fun or engaging problem. Sometimes the request is framed around a type of document, like a memo or appellate brief, and sometimes it is framed around an area of law, like negligence. Though there is nothing inherently problematic about a generalized request, a more targeted inquiry into learning outcomes or pedagogical goals would yield problems better aligned with the requesting professors’ objectives.

Ultimately, these requests suggest that many professors are seeking an engaging problem that is tried and true—something that has been vetted and worked well in the past—and that effectively imparts specific knowledge to the students. A well-vetted problem means less risk for the professor adopting the problem because it is unlikely that unexpected issues will arise to interfere with students’ learning processes. But just because a problem has been vetted does not mean that it is necessarily suited to the requesting professor’s pedagogical goals or that it will impart the desired knowledge to the students.

This Article addresses this disconnect by asserting that framing problem-design discourse around rule structure aligns pedagogical goals with the problem. Rule structures vary in complexity, and it is that complexity that governs the overall difficulty of the assignment, not necessarily the source of law or genre. Rule structure is intimately tied to the various pedagogical outcomes taught in a first-year legal writing course, such as organization, rule synthesis, styles of legal reasoning, and so forth. It should go without saying that the purpose of a writing assignment is to teach discrete outcomes in an experiential way. Thus, once the desired outcomes have been identified, the first step in problem design should be to identify the rule structure that best accomplishes those outcomes.

To ensure a better match between problem and pedagogical outcomes, this Article establishes common terminology linking rule structure to discrete outcomes to support a sophisticated and disciplinary approach to problem design. Six basic rule structures exist: simple declarative, conjunctive (sometimes called elements), factors (sometimes called totality of the circumstances), balancing, disjunctive (sometimes called either/or), and defeasible (sometimes called rule with exception).[9] These rule structures are explained in detail in Section III, infra, and catalogued according to the pedagogical outcomes that are well-suited to problems designed around each rule structure. Because assignments are formative, not just summative, professors should identify the outcomes associated with any problem they choose to use and understand how designing a problem around rule structure can achieve the desired outcomes. Developing problems around rule structure is a reliable way to ensure the desired learning outcomes or pedagogical goals can be achieved through the problem.

The objective of this Article is to elevate and revolutionize the discourse surrounding problem design; in addition to, or even instead of, seeking an engaging fact pattern, or a “good memo” problem, or a problem involving “X” area of law, problem creation and selection should focus on rule structure to be more specifically tailored to discrete pedagogical goals and learning outcomes. In this way, the problem can be engineered to involve concepts that are appropriate given the students’ experience.[10] When a problem is designed around specific learning outcomes, it is more likely to be suited to students’ knowledge level, thereby ensuring that the writing itself “becomes an integral part of [their] thought” processes.[11]

Obviously, this Article is not the first to claim that problems should be intentionally designed around learning outcomes. Bannai et al., have advised that legal writing professors should “(1) teach, and allow students to practice, specific skills; (2) be neither too difficult nor too easy; (3) involve subjects that are interesting, familiar, and realistic; (4) be well researched; and (5) be sensitive in its treatment of issues and individuals.”[12] Kintzer et al., have also written that rule structure should be considered when designing problems.[13] This Article takes their suggestions further by mapping rule structure to specific outcomes, making the process of problem design more intentional and the outcomes more predictable.

This Article relies on best practices and modern pedagogical theory to assert that the problems used in legal writing courses should be intentionally designed around specific rule structures to achieve discrete learning outcomes, and treat source of law, jurisdiction, genre and area of law as secondary concerns. Section I explains the purpose of the problem as an integrated learning experience. Section II explores the foundations of problem design. Section III provides a framework and process for effective problem design using rule structure to synchronize the problem with the desired learning outcomes.

I. Why Does Problem Design Matter?

Problems are the principal pedagogical apparatus of the legal writing professor because the problem facilitates the teaching of how lawyers think and what lawyers do.[14] Problems are substantive in that they teach students that (1) the recursive writing process involves the overlapping and intertwining of pre-writing, writing, and revision; (2) legal “writing is rhetorically based, focusing on audience, purpose, and constraints”; and (3) the final product must simultaneously “communicate[] the writer’s message [while meeting] the reader’s needs.”[15] More specifically, the problem is not merely a summative instrument used to measure whether students have grasped a concept; rather, the problem is the formative instrument students use to grasp particular concepts because, through writing, students learn the conventions of the discourse community.[16] By learning these conventions, students learn more than how to produce documents in a particular genre; they learn when and how to adapt these conventions to new rhetorical situations.[17]

Within the discipline, methods for designing problems have not evolved consistently alongside legal writing pedagogy. Early on, “writing was thought of as separate from analysis and the focus was on practical knowledge development: teaching students how to produce legal memoranda, briefs, etc.”[18] Known as the “product approach,” this method treats legal writing instruction as a mere skill, not disciplinary learning.

Related to the product approach, many programs distinguish between objective or predictive writing and persuasive writing, often teaching them in different semesters.[19] In the predictive semester, assignments tend to focus on the internal office memorandum, a document some argue is practically obsolete[20] although it may endure as a sound pedagogical tool,[21] and the persuasive semester often focuses on the appellate brief.

These approaches that focus on product and predictive vs. persuasive writing, however, miss the point of what legal writing programs should be teaching.[22] Regardless of the product[23] or the predictive/persuasive distinction, to teach the recursive writing process, rhetorical strategies, and effective communication, professors must give considerable thought to the substantive problems they design, not just the product they ultimately want the students to produce.[24] As a result of the scholarly discourse that has evolved in the legal writing community, the field as a whole has developed into a robust discourse community that recognizes analysis occurs through the process of writing, and the discipline appreciates that learning how to engage in the rigorous analysis of complex legal questions is more than just a skill.[25] Even though the problem supports disciplinary learning,[26] however, scholarship on best practices in problem design has not been prolific in the way that other scholarship has been within the discipline.

Looking through a disciplinary lens, the problem is an essential method by which law students are initiated into the discourse community. When problems are designed around rule structure, outcomes can be scaffolded in a way that more intentionally teaches the conventions of the discourse community, “enabl[ing] [students] to structure and process their thoughts effectively.”[27] “Scaffolding” is “an instruction device that provides individual students with intellectual support so they can function at the cutting edge of their cognitive development.”[28] Scaffolding empowers students to take greater ownership of their learning, as it renders information processing a more manageable task.

In the context of problem design, scaffolding simply means beginning with simple rule structures before introducing more complex ones. Simple rule structures, like declarative rules and elements tests, are more conducive to learning early in students’ law school careers because they are easier to manage and understand. These simpler rule structures map to less complex learning outcomes like rule identification and rule-based reasoning. They also create knowledge upon which students can connect new understanding about legal discourse.[29] As students gain fluency in the discourse, they are better able to navigate problems designed around more complex rule structures because they can relate the new material to what they have already learned.[30] This structured approach allows students to learn incrementally so that they can “internalize the fundamentals which will enable them to successfully approach legal problem solving and expression.”[31]

For these reasons, a problem designed around rule structure and learning outcomes “help[s] legal educators link what lawyers know to what lawyers do.”[32] It more explicitly teaches students the conventions of the discourse community, including, but not limited to, the cognitive thought processes essential to lawyering.[33] In this way, students are taught to “look behind the product [to] develop an understanding of how and why [it] came into being.”[34] As a result, students are better prepared to translate what they learn in law school to the demands of actual practice.[35]

Legal writing professors have a duty to teach their students how to think and write well for the practice of law.[36] This duty is most predictably fulfilled by developing problems around rule structure because this approach makes it more likely that concepts are strategically introduced and reinforced through the simulated setting. In other words, when problems are intentionally designed around rule structure, students can more readily learn how to adapt their basic skills in increasingly sophisticated ways. They should also gain confidence in mastering the basics and feel more comfortable translating those basics into contexts that require more complex analyses. Deliberately crafting problems around rule structure is the most reliable way to precisely achieve desired outcomes such as fluency in legal discourse and transfer of knowledge and skills to a variety of rhetorical contexts.

To create a problem that is truly an integrated learning experience, providing both sound formative and summative assessment of student learning,[37] it is necessary to consider the ultimate goal(s) of the assignment, which must be rooted in the goals of legal education, generally. The general goals of legal education, to a large degree, are to introduce students to the discourse community and teach them to utilize the language and systems of the community.[38] This is often referred to as teaching students to “think like lawyers.”[39] The ABA Sourcebook on Legal Writing[40] identifies the following skills that should be taught in a typical first year writing course:

RESEARCH:

-

Court System Structure (State, Federal, and Tribal)

-

Common Law Process

-

Primary and Secondary Authority

-

Mandatory and Persuasive Authority

-

Manual and Online Research, including Updating Authority

-

Ethics

ANALYSIS:

-

Identifying Issues

-

Reading and Briefing Cases

-

Statutory Interpretation

-

Weight of Authority

-

Synthesizing and Explaining Rules

-

Applying Rules to Facts

-

Reasoning, including Rule-Based, Analogical, Counteranalogical, Policy, Principle, Custom, and Narrative

-

Rhetorical Theory

-

Developing a Theory of the Case

-

Analyzing Unsettled Rules of Law

-

Rule Structure

PERFORMANCE:

-

Predictive and Persuasive Writing

-

Document Genres, including Memos and Appellate Briefs

-

Drafting, including Grammar, Paragraph Structure, Sentence

-

Document Organization

-

Oral Argument

-

Organizational Paradigms such as IRAC, CREAC, CRuPAC, TREAT, and so forth

-

Articulating a Thesis

-

Questions Presented and Brief Answers

-

Fact Statements

-

Citation

-

Plagiarism

-

Standard of Review

-

Audience

-

Paragraph and Sentence Structure

-

Revising and Proofreading

-

Narrative and Storytelling Techniques

Rooted in these outcomes, the legal writing classroom, like other first-year courses, trains students to find and make meaning out of the law.[41] Traditional legal rhetoric, for example, expects arguments to take a particular form, the syllogism, which Aristotle considered to be “the structure that produces new knowledge.”[42] In addition to teaching traditional legal rhetoric, many legal writing professors are justifiably concerned with teaching “cross-cultural competency [for] professionally responsible representation and . . . promot[ing] a justice system that provides equal access and eliminates bias, discrimination, and racism in the law.”[43] Importantly, throughout their legal training, not only must students learn to identify meaning within the law as it exists, but students must also learn that becoming a lawyer imbues them with the power to create legal meanings that affect the material and social reality of others.[44]

Certain rule structures are well suited to reinforcing traditional legal rhetoric[45] while others are better suited to teaching students how to challenge traditional legal rhetoric,[46] which was designed to reinforce the status quo, not to achieve equity or eliminate bias, racism, and injustice.[47] By centering rule structure as the first consideration in problem design, the professor can strategically consider how best to accomplish the particular learning outcomes associated with training students to find and make meaning out of the law, whether by challenging or reinforcing traditional legal rhetoric.

When designing a problem, the professor should have in mind which outcomes will be taught and assessed through the problem. Writing experiences must be scaffolded so that problems assigned early in the semester are designed around simpler skills and later evolve to incorporate more complex ones.[48] Professors must strive to create problems that are, to quote Goldilocks, “just right”: not too complicated (to avoid cognitive overload)[49] and not too simple (to avoid cognitive underload).[50]

It is axiomatic that the rule structure of problems impacts student learning; solving the problem itself and expressing the solution in writing and orally is the learning.[51] Certainly, a student is not going to learn legal writing by exclusively reading samples and listening to lectures,[52] and mere exposure to the legal writing discipline will not necessarily cause students to become fluent in the discourse.[53] They must wrestle with the concepts in a hands-on way through analyzing the issues in the problem, researching the law, synthesizing the law to coherently examine the issues, and actually writing about it.

Rule structure governs how the problem is resolved and how the written product is organized, so it must be at the forefront of the professor’s mind from the very beginning.[54]

II. Foundational Considerations in Problem Design

The few resources that explain how to design legal writing problems have historically viewed the law “as a fungible aspect . . . that varied based on skills-based pedagogical goals.”[55] Most advise professors to choose a substantive area of law that first-year students can comprehend without consideration of the rule structures relevant to solving the particular issue presented in the problem.[56] Even the articles that advise professors to choose problems based on the rules’ organizational approach do not spend time explaining the various rule structures or identifying the structures that are best suited to teaching particular concepts.[57] Indeed, there is even disagreement about what disciplinary writing should be.[58]

Many articles that tackle problem design simultaneously address other issues, such as curriculum, course design, and the legal writing discipline as a whole.[59] Consider the 1997 essay by Grace Tonner and Diana Pratt, Selecting and Designing Effective Legal Writing Problems.[60] It demonstrates how attempts to provide concrete advice on problem design ultimately function more as a guide to course sequencing rather than problem design.[61] Since 1997, just one article has expressly argued that (1) rule structure should be considered when designing problems; and (2) assignments should progress from simple to complex.[62] But that article does not define what it means by “simple” and “complex,” and it also mixes the ideas of rule structure, common law and statutory law, and state and federal law, without identifying a central driving consideration or guiding the reader in how to prioritize competing considerations.[63]

The differences in state and federal law or common and statutory law are not meaningfully significant vis-à-vis learning outcomes.[64] Thus, changes in state and federal law or common law and statutory law, from a problem design perspective, cannot be primary drivers of pedagogical outcomes. For example, rule-based reasoning is an outcome that can be taught through either statutory law or common law because rules can be derived from either statutes or cases.

Similarly, rule synthesis is an outcome that can be taught using virtually any set of cases, regardless of whether the cases raise federal or state law questions. By designing around rule structure, the professor can scaffold student learning by keeping in mind that synthesizing a simple declarative rule is inherently simpler than synthesizing, for example, a factors test. As explained in more detail in Section III(C), infra, factors tests often involve multiple components, and courts do not necessarily articulate the specific factors; instead, they often articulate the facts that influence the holding, leaving the reader to label the broader categories or factors. The complexity of the case set is thus rooted in the rule structure itself, not in the jurisdiction. Although jurisdiction or source of law could potentially influence the difficulty level of the problem, these concerns are secondary to the complexities inherent in the rule structure itself.

Another issue that arises in the existing literature is that it tends to focus on the various documents that can be created (such as a predictive memo or appellate brief), rather than on how problem design facilitates student learning.[65] As mentioned in Section I, supra, this is known as the traditional product approach, which treats legal writing as a mere skill rather than as disciplinary learning, prioritizing document production over skill mastery.[66] The traditional product approach assumes that producing legal documents inevitably leads to skills mastery. It obscures the fact that the purpose of the problem in a legal writing classroom is to teach students how to answer complex legal questions, using legal documents as a tool to coherently express the solutions to those complex legal questions.[67]

The existing literature also advises prioritizing the area of law over rule structure. Some of the literature advises choosing something familiar and derived from, inter alia, “first year courses, . . . [t]reatises[,] . . . [or] [o]n a more popular level, . . . the news media.”[68] Other sources inform that topics are selected “specifically to avoid duplicating issues covered in other first-year courses, partly in order to expose students to an area of law they are not already studying and may not have a chance to study before they graduate.”[69] While, of course, the subject chosen for a legal writing problem is inevitably bound to produce deep knowledge in students about that subject, producing that deep knowledge is not the primary purpose of the legal writing course. Rather, it is merely “incidental declarative knowledge,”[70] a tool to facilitate learning how to engage in legal analysis to solve complex legal problems.

Incidental declarative knowledge should never be the principal consideration in problem design, however. Instead, the most important consideration in problem design must be the acquisition of deliberate declarative disciplinary knowledge, including, but not limited to, legal analysis as expressed orally and in writing.[71] The best way to ensure students acquire this deliberate declarative knowledge is to design the problem around rule structure.

None of this is to say that jurisdiction, source of law, genre, or area of law are wholly irrelevant. The point is that those considerations should not be the primary catalyst of problem design. An approach that focuses on these extraneous considerations does not place learning outcomes at the center of the inquiry, inevitably leading to inconsistent results from year to year because it “ignore[s] the core question of what students are learning”[72] and how the problem advances those learning goals.

Rule structure influences the available analytical, rhetorical, and organizational choices available to solve the legal problem and drives the way that students will think through solutions to the problem. For these reasons, it must be the foremost consideration in problem design. The other potential complexities, such as jurisdiction, source of law, area of law, and genre, should be considered only after the rule structure is selected and the problem begins unfolding.

Building a problem around rule structure ensures that students deliberately acquire disciplinary knowledge, which “is necessary for deep learning [of the law and legal conventions] . . . [as it] is how new members of the discipline become literate in that discourse community.”[73]

III. Designing a Problem Around Rule Structure

This section emphasizes the process of designing a problem from scratch, but these considerations also apply when adopting an existing problem. After all, even when adopting an existing problem, there is often a need to modify the problem to better fit the needs of the class and to adapt to changes in the law.[74] Whether creating a problem from scratch or adopting a pre-existing problem, it is important to consider the desired pedagogical outcomes and how the problem fulfills those outcomes. The most reliable way to connect outcomes to the problem is to develop the problem around rule structure.

The field of Mind, Brain, and Education informs that “[s]kills grow in three cycles, moving from single elements to complex systems for first actions, then representations, and then abstractions.”[75] Learning in law school, much like in every other learning environment, is equally “slow and hard,”[76] and requires coordinating the learning of necessary skills with the ever-changing developmental process.[77] Formative assessments must be balanced to sufficiently challenge students without overloading them with material that is too advanced.[78] Thus, legal writing problems must be designed to begin with simple elements and then progress to more complex systems throughout the course. This progression can be accomplished by designing problems around rule structure and then tailoring the other components (such as facts, jurisdiction, source of law, and genre) to meet any other pedagogical goals of the assignment. By designing problems in this way, instruction can be scaffolded, beginning with the most foundational concepts, and then progress based on students’ increasing knowledge throughout the semester. In this way, the cognitive load is well-managed to ensure that students are neither overloaded nor underloaded.

The six rule structures, in order of least complex to most complex, are: simple declarative, conjunctive (also known as an elements test), factors (also known as a totalities of the circumstances test), disjunctive (also known as an alternatives or either/or test), balancing, and defeasible (also known as a rule with exception).[79] These rule structures may also be combined. For example, a balancing test may demand consideration of factors on either side of the balance, or a conjunctive test may incorporate disjunctive elements. The following order accounts for increasing cognitive demands of each rule structure.

-

Simple Declarative Rule. The simple declarative rule is perhaps the most obviously simple structure. It inherently deals with one thing, usually a prohibition, and it does not depend on the interpretation of other parts of the rule to give it meaning.

-

Conjunctive Rule. The conjunctive test comprises more than one simple declarative rule joined by “and.” The conjunctive test is more complex than the simple declarative rule because it has more pieces, but it is still a fairly simple structure in that it essentially creates a positive checklist whereby proof of each element satisfies the test.

-

Factors Rule. The factors test is more complex than the conjunctive rule even though it, too, comprises more than one simple declarative rule because it requires the writer to exercise judgment in determining which factors are salient, how they relate to one another, and how they govern the solution to any given problem. A factors test requires a totalities perspective because not every factor will always be relevant to a given fact pattern, and factors will carry different weights depending on the different factual scenarios. Unlike the conjunctive test, the writer cannot simply create a checklist to be examined. Instead, the writer must consider a more comprehensive picture.

-

Disjunctive Rule. The disjunctive test requires students to analyze two or more separate branches of a rule, taking into account not only competing interests but also contingencies and competing rules. Because of the sheer number of potentialities, this rule structure creates layers of complication in both organization and analysis. Importantly, the complexity of a disjunctive test is malleable. For example, a problem might easily be written so that the disjunctive part of the statute is eliminated from the analysis, or the only issue presented for analysis might be resolving which side of the disjunction applies in a given factual scenario.

-

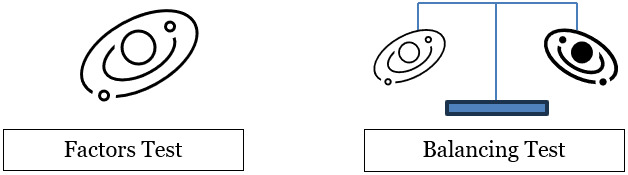

Balancing Rule. The balancing test, like the factors test, requires the writer to exercise professional judgment, but adds in a layer of addressing competing interests at the same time. While factors tests require balancing of the factors with each other, that “balancing” is fundamentally different than a balancing test where there are two or more competing interests that have to be balanced against each other. The below images are illustrative. On the left, a factors test is represented by a single concern at the center with the smaller circles representing two particularly strong factors and the elliptical lines representing the totality of the circumstances that must be considered. In other words, a factors test exists within its own universe. On the right, the balancing test looks more like a balancing scale with two universes, one on either side, with unique competing interests, not a central unifying concern.

- Defeasible Rule. The defeasible rule is challenging for writers because it involves an exception, which demands defining not only what belongs, but also what does not. Identifying and justifying what does not belong is an added layer of complexity when compared to other rule structures that require basic identification of what does belong.

When designing problems, professors should begin with the simplest rule structures and then progress to more complex structures. If students are required to analyze more complex rules before they learn how to analyze more basic rules, they will not have the necessary cognitive receptors upon which to create sophisticated thought patterns. For this reason, starting simple is essential.

A. Start Simple: Declarative Rules

Simple declarative rules are fundamental rule structures that effectively introduce students to the concept of rule-based reasoning, perhaps the most foundational mode of legal reasoning.[80] The simple declarative rule is the building block of every other rule structure that exists. A conjunctive test, for example, is essentially two or more simple declarative rules joined together by “and.” Each factor in a factors test is its own simple declarative rule joined by “or,” any combination of which could satisfy the test. Either side of a balancing or defeasible test can likewise be reduced to a simple declarative rule or series of simple declarative rules. Teaching students how to analyze and understand simple declarative rules is thus essential to preparing them to analyze more complex rule structures.

Often, simple declarative rules are written as prohibitions like “no littering” or “no smoking.” These are the kinds of rules that new law students can understand easily based upon their prior life experiences. In using a simple declarative test, the professor would generally have no concerns about students being too overwhelmed by learning complex legal standards while at the same time learning the nuances of written and oral advocacy.[81] The risk of cognitive underload tends to arise only if students are required to continue working on simple tasks after they have become proficient or if the fact pattern is so overly simplified that students struggle to buy in. So, although simple declarative rules, upon first examination, may seem overly simple even for novice legal writers, they actually present the perfect level of difficulty to challenge students to begin engaging with legal analysis while building confidence in their learning of foundational concepts.

A simple-declarative-rule problem also reinforces to students the importance of incorporating rule-based reasoning into their analysis and not relying exclusively on analogical or counteranalogical reasoning. Students who rely heavily on analogical and counteranalogical reasoning, to the exclusion of other modes of reasoning, tend to case brief instead of synthesize a coherent rule of law. They may also struggle to explain why a certain argument is correct given the rhetorical circumstance. If they start with a simple declarative rule and rule-based reasoning, however, they are trained to think first about rule-based reasoning, and their use of precedent is more intimately tied to explaining the rule, not just regurgitating precedent facts for the purpose of drawing comparisons that may or may not be salient.

The case-briefing phenomenon occurs as a result of cognitive overload when students are asked to synthesize too soon before they have learned how to identify and work with rules and rule structure.[82] As novices, the process of rule synthesis can seem like a simple exercise to students that merely involves identifying similarities and differences between precedent and the hypothetical fact pattern. These concepts of analogy and counteranalogy are often familiar to students from their prior life experiences. Additionally, students feel comfortable writing about the facts because that part of the assignment feels more familiar and connected to their lived experiences. But even though they understand the “what”—similarities and differences—they do not necessarily grasp why the similarities and differences matter.

In a legal writing course, because students do not yet know how to effectively distinguish between the “material and immaterial,”[83] they do not fully understand that every similarity is not necessarily legally significant or that every difference is not salient. Thus, they resort to case briefing, throwing every fact from precedent into the explanation, and then comparing every fact to the hypothetical fact pattern without regard for whether the fact is legally relevant or outcome-determinative.[84] By beginning with a simple declarative rule and rule-based reasoning (using a problem that does not require synthesis from multiple sources), students learn the importance of identifying authority to support their arguments and how to make arguments without resorting to superficial factual comparisons between the hypothetical problem and precedent.

Rule-based reasoning requires students to think beyond mere observations so that when they begin learning analogical and counteranalogical reasoning, they have the foundation to understand that more than mere observational comparison is required. Learning how to work with the rule, therefore, is a critical step in teaching students how to distinguish between the material and immaterial.

Turning to how to design the problem, the first step is to identify the rule. Good sources for simple declarative rules include quasi-legal sources, like employee manuals, honor codes, and school discipline policies, as well as actual legal sources like criminal laws and rules of procedure.

A simple-declarative-rule problem aligns well with the following outcomes:

-

Identifying rule structure

-

Explaining the rule

-

Rule-based reasoning

-

Canons of statutory interpretation, such as reading statutes in pari materia

-

Symmetrical organization

Depending on the overarching pedagogical goals, once the rule has been selected, the professor has significant freedom to craft the problem in a variety of ways. One consideration may be that the professor does not want students to write an entire traditional memo early in the semester. The simple declarative rule can easily be used to create in-class exercises or shorter analytical assignments like an email memo.

Simple-declarative-rule problems are easiest to build using statutes, rules, or regulations, not cases, and a common feature of the simple-declarative-rule problem is that it limits sources of law to a code or set of rules. This type of problem should not require students to engage in reading cases, briefing cases, or synthesizing rules. Instead, students learn the tenets of statutory interpretation, like reading statutes in pari materia, along with rule identification and explanation, rule-based reasoning, and organizational paradigms.

Once the central rule is identified, creating facts to be analyzed is not difficult. Consider, for example, a problem built around a rule that prohibits drinking contests.[85] The simple declarative rule might be, “Drinking contests are prohibited.”[86] The fact pattern could involve an event hosted by a student group where the facts ambiguously establish a “contest” situation. Students would be required to wrestle with how to define “drinking contest” and then apply the rule to the facts of the hypothetical. The definition of “drinking contest” could be derived from other rules within the policy or through a dictionary or any other source the professor authorizes.

The key to making a simple declarative rule work is keeping the analysis narrowly confined. For a problem built around this rule: “Smoking [is] prohibited in all enclosed public places,”[87] the fact pattern could be built around the question of what smoking means. For example, is vaping “smoking” within the meaning of this rule? Alternatively, the fact pattern could be built around the question of what “enclosed public place” means. For example, is a patio area “enclosed” during the winter when vinyl barriers are in place to protect diners from the elements? The problem should not, however, be written around both questions at once, especially not early in the semester before students have gained fluency in the fundamentals of legal analysis.

This same rule, however, could effectively be used to teach the concept that a rule must be explained in the way that it will be applied. For example, students could be presented with a fact pattern involving the question of whether “vaping” means “smoking” within the meaning of this rule. After completing that analysis, they might receive a follow-up assignment asking them to analyze a fact pattern involving a patio that may or may not be “enclosed” within the meaning of the statute. The idea that the law must be explained as it will be applied is a challenging concept for novices to understand, and using a simple declarative rule with a fact pattern that deploys varying permutations sequentially is an effective way to teach it.

Initially, students may feel frustrated by exclusively operating within the confines of a code or set of rules. They may struggle to understand how to explain a rule of law without being able to compare it to other precedential scenarios. Eventually, however, they realize how important it is to be able to explain every facet of the rule before resorting to factual comparisons with precedent. By requiring them to follow this process, students generally do not lapse into a series of case briefs in their subsequent assignments, and their legal analysis usually includes detailed rule and sub-rule statements that anchor the analysis.

The ability to state a rule and analyze it independently of precedent is a critical foundational concept without which students will struggle to master explanatory synthesis. The simple-declarative-rule problem teaches students the importance of developing a strong analytical framework through the articulation of the rule. Once the framework is established, they can use precedent to draft case illustrations to support the framework. By using a simple-declarative-rule problem that requires students to engage in rule-based reasoning, the professor builds “muscle memory” so that students know how to draft strong analytical frameworks.

Because rule structure dictates the overarching organization of the analysis, teaching students rule-based reasoning first permits the professor to focus on the simplest organizational paradigms. Problems built around simple declarative rules also help students gain fluency with the legal syllogism, and using a full-fledged simple-declarative-rule problem early in the semester introduces essential content such as issue statements, brief answers, fact statements, organizational paradigms, and conclusions as well as substance such as statutory interpretation, rule identification, rule explanation, and rule-based reasoning.

Finding simple declarative rules can sometimes be challenging because the law is complex, and statutes frequently establish more complicated rule structures.[88] Even within the criminal code, for example, many criminal statutes involve elements tests, disjunctive tests, or even combinations of these. City and county ordinances tend to be simpler, and even quasi-legal rules, like those found in honor codes or student handbooks are commonly written as simple declarative rules. Additionally, procedural rules often follow the simple declarative rule structure and have the added advantage of helping students gain an understanding of legal processes early in their legal career.

Initially, it may seem boring to build an entire memo problem around a simple declarative rule. It may also seem like there is not enough time during the semester to focus an entire problem around rule-based reasoning, but it is worth doing because the concept is so very foundational. Investing this time in the foundations ensures that students are well-prepared to advance to more sophisticated concepts.

To be sure, rule-based reasoning can be taught in other ways. For example, if a memo problem involves a conjunctive test, the professor may choose to take one element and use that as a formative assessment tool for teaching rule-based reasoning. These minor assignments represent chunks of learning that are manageable for students and teach them how to translate their newly learned skills in different settings. Furthermore, smaller assignments involving rule-based reasoning are easy to incorporate as in-class assignments because they do not necessarily require much time to complete.

To summarize, the use of a simple-declarative-rule problem early in the semester permits students to practice articulating and explaining rules and deploying rule-based reasoning, both of which are foundational and substantive. This method trains students how to identify relevant details and then use those details to examine fact patterns. It reinforces the idea that legal analysis should be rooted in authority, which is typically articulated as a rule in legal discourse.

B. Continue to Build: Conjunctive Tests

After the simple declarative rule, the next easiest rule for students to understand is the conjunctive test. Essentially, a conjunctive test is a series of simple declarative rules strung together with “and.” If a student understands simple declarative rules and rule-based reasoning, those skills can easily be adapted and applied to conjunctive tests. When designing problems, professors should be cautious about whether any element has embedded a more complicated test. If a conjunctive test involves three elements, but one element requires students to consider multiple factors, the students may be confused because they have not yet learned how to analyze and organize around a factors test.

This issue is not necessarily fatal—perhaps the factors are not complicated, and the professor can dedicate time in class to guiding the students through organization of a factors analysis. Another option is for the professor to exclude the factors element from the analysis by instructing that the element is not at issue and that students should analyze the other elements. It is important to remember, as well, that the sub-rules do not drive the overall analysis; they only apply to narrow aspects of the overall analysis. The overarching rule structure will drive overall organization and determine the styles of legal reasoning available to the writer, whereas the sub-rules will govern, at most, the rhetorical options available for a single section. Ultimately, the professor should consider the pedagogical goals, such as the style of reasoning, the type of rule identification and synthesis, and the style of organization, when deciding whether an elements test that has other embedded rule structures is manageable for the class.

Conjunctive tests build on the foundation students learned with the simple declarative rule. A conjunctive test will again require students to identify and explain governing rules and sub-rules, but the test is generally more complicated because there are more pieces to coordinate as a single, comprehensive rule. This single rule, however, can generally be treated as a checklist of simple declarative rules, meaning that the analysis will have a fairly predictable organizational structure including at least one paragraph of explanation per element. At this stage of their education, students should be able to chunk each piece of the elements test and address them one at a time.

The chunking of the elements into separate declarative rules reinforces the foundation established with the simple-declarative-rule problem and adds the new concepts of rule synthesis, analogical reasoning, and counteranalogical reasoning. Rule synthesis is the process of combining information from various legal sources, such as statutes, cases, rules, and policies, to articulate a generally applicable rule or subrule. The product of rule synthesis appears in the rule explanation section of the analysis. Analogical and counteranalogical reasoning is found in the application section of the legal analysis, and it draws comparisons and distinctions between precedent facts and the facts of the hypothetical case. Through analogical and counteranalogical reasoning, students can identify similarities and dissimilarities that should help them predict a likely outcome in a particular case.

Even adding in rule synthesis, analogical reasoning, and counteranalogical reasoning, students must continue to include rule statements and rule-based reasoning. Rule synthesis, analogical reasoning, and counteranalogical reasoning build on the foundations of rule statements and rule-based reasoning to provide a richer understanding of how the rule operates.

When crafting a conjunctive-test problem early in the first year of law school, the facts should not be overly complicated, and they should generally only call one element into question. This narrow focus allows students to continue building on the foundational skills in a way that does not create cognitive overload. Creating research assignments around this type of test is also fairly easy because the annotated statute is likely organized around the elements. Not only can the professor easily read the precedent related to each element and then decide which element will be most manageable given the students’ experience and available authority, but students will be able to identify a good starting point for the research on their project.

Consider, for example, an elements test defining murder as “[t]he unlawful killing of a human being [w]hen perpetrated from a premeditated design to effect the death of the person killed.”[89] Taking inspiration from precedent, the professor could build a fact pattern that calls into question “premeditated design,” while including facts that obviously meet the legal standard vis-à-vis the other elements. This fact pattern would make it obvious that someone has been killed by someone else without permission or justification, and the only question would be whether the killer premeditated the killing.

Conjunctive rules layer learning upon the foundations established with the simple declarative rule using the new concepts of reading cases and synthesizing rules from precedent. Because students have learned the fundamentals of identifying and articulating rules, they should understand that they must articulate coherent rules and sub-rules, even when they are synthesizing those rules from precedent. In this way, they can avoid case briefing, a common pitfall in the early stages of learning rule synthesis. Effective rule synthesis demands that students carefully consider the purpose and function of each sentence of rule explanation. Each sentence of rule explanation should fulfill at least one of the following purposes: elucidation,[90] elimination,[91] affiliation,[92] or accentuation.[93] A sentence may even fulfill more than one purpose.

Conjunctive rules also layer new styles of reasoning on top of the foundational rule-based reasoning learned through the simple-declarative-rule problem. Sophisticated legal analysis employs a variety of reasoning styles, but students cannot learn all the various styles at one time. Gaining fluency in the most basic form, rule-based reasoning, is essential to establishing a foundation for the more sophisticated styles like analogical, counteranalogical, narrative, and others. By beginning with a simple declarative rule, students learn that articulating the rule and utilizing rule-based reasoning are essential first steps to effective legal analysis. This foundation helps them avoid another common pitfall of simply comparing the facts of their problem to the facts in precedent without tethering the comparisons to any sort of analytical framework.

The other benefit of creating a problem around a conjunctive test early in the first year is that it tends to be easily organized within the traditional IRAC paradigm that first year law students must learn to perform well in law school. The test itself functions as a type of checklist wherein each element can be fully explained before the entire test is applied to the fact pattern. It is not hard to hold the explanation for each element in short-term memory, and in fact it is generally helpful for the reader to have a comprehensive understanding of the legal test as a whole before it is applied to the hypothetical. Often, a single fact in a hypothetical will impact the analysis of more than one element. By maintaining a strict IRAC structure wherein each element is explained entirely before any application is conducted, the writer avoids unnecessary repetition of the facts as they may apply to each element.

The conjunctive test also offers flexibility to begin teaching some variations in organizational paradigms. For conjunctive tests with elements that are not factually intertwined, the conjunctive test can be used to teach students how to analyze each element discretely through subsections that include a comprehensive explanation and application of the individual elements treated within each subsection. If one of the pedagogical goals is to teach this organizational variation, the professor must study the relevant body of caselaw carefully to ensure that the analysis of each element is not so intertwined that students would face difficulty in separating the analysis.

Consider a problem built around “assault” defined as “an intentional, unlawful threat . . . to do violence to the person of another, coupled with an apparent ability to do so, and doing some act which creates a well-founded fear in such other person that such violence is imminent.”[94] Much of the caselaw interpreting this statute intertwines the analysis of each element such that separating them into subheadings becomes virtually impossible.[95] The intent to threaten harm depends largely on whether the threat has been accompanied by some overt act evidencing the apparent ability to carry out the threat.[96] Similarly, whether the purported victim’s fear is reasonable also depends on whether there has been some overt act evidencing an apparent ability to carry out the threat.[97] This particular elements test, therefore, works best for reinforcing one large IRAC organizational paradigm rather than an organizational scheme utilizing subheadings and a series of mini-IRAC sections.

In developing a problem around a conjunctive test, the professor must carefully consider the depth and breadth of knowledge the students possess, and tailor the problem to meet their cognitive-load needs and demands. The professor must consider how many elements should be at issue in the problem, how the caselaw treats each element, and whether the elements can easily be separated or whether they should be explained all together. Once the rule is identified, the professor should study the body of available caselaw and begin drafting a fact pattern that intentionally aligns with the sources available for analyzing the issues.

To summarize, the conjunctive test builds on the simple declarative rule test by adding on multiple simple declarative rules. This rule structure is also conducive to introducing rule synthesis, analogical reasoning, and counteranalogical reasoning. The layering of these new concepts upon the foundation of rule identification and explanation and rule-based reasoning allows students to learn at an appropriate pace in terms of their cognitive development.

C. Layering Learning: Introducing the Factors Test

The factors test adds a layer of complication even though it may initially appear to be similar to the conjunctive test. Like a conjunctive test, the factors test is made up of several simple declarative rules, but the fact that they are joined together by “or” instead of “and” is a critical difference that creates challenges for organizing the factors analysis in the form of a checklist. A checklist dissuades a comprehensive analysis by obfuscating the interrelated nature of the factors. The checklist does not effectively demonstrate that the factors test is a cohesive rule of law synthesized from diverse cases, where any given case may not involve each factor relevant to the given hypothetical problem. Students are required to exercise more judgment in terms of organization with the factors test than they must exercise with the conjunctive or simple declarative rule because they cannot necessarily address one factor at a time. Determining how to address each factor requires exercising the judgment that they have learned by practicing with simpler rule structures, like the simple declarative rule and the conjunctive test. The key feature of the factors test is that the factors are interconnected, and their relationship to each other, not a single individual factor, generally determines the outcome. So, instead of holding one piece of the test at a time, students must hold multiple pieces at once and manage the ever-shifting connection between the factors and their relation to the overarching legal standard.

Factors tests are frequently embedded in other rule structures. For example, a balancing test might have factors on either side of the balance that must be weighed. In section III(E), infra, balancing tests are examined in more detail. When the factors test is embedded in another rule structure, the organizational decisions the student must make are even more complicated.

Synthesizing a factors test can also be complicated when the factors test is embedded in precedent, as opposed to explicitly created through a statute or rule. It is not uncommon for an opinion to articulate facts and then jump to the holding without expressly naming the factors, leaving students in a position where they must identify and label the factors that the courts have implicitly used to guide their analysis.[98] This process requires students to engage in inductive reasoning to identify patterns in precedent and define categories that govern the legal analysis. Michael R. Smith explains that

[t]he types of legal issues that give rise to the inductive reaction of a factor test have two general characteristics. First, the law on an issue must set out some kind of flexible legal standard designed to control the outcome on the issue. Second, a number of cases must exist in which the courts of the jurisdiction endeavored to apply the flexible legal standard to the facts of specific cases.[99]

Deriving a factors test from precedent is an advanced form of inductive reasoning that requires students to possess a strong foundation in identifying and explaining rules and subrules, and it also requires students to manage a large body of precedent governing the issue. That is why teaching the factors test after students have analyzed a simple declarative rule and a conjunctive test is a sound strategy for ensuring long-term proficiency in the various legal writing outcomes.

It is challenging, if not impossible, for students to move beyond basic fact-to-fact comparisons with precedent and articulate a coherent analytical framework if they have not yet learned how to articulate and explain simpler analytical frameworks. When articulating a factors test, students may be working with a set of cases that do not expressly acknowledge that a factors test governs the outcome. The court may only say that it considered certain facts to be particularly important, and then students would need to label these facts in a way that creates categories in order to articulate a clear rule and establish a strong analytical framework.

In the following example, none of the cases cited specifically names these factors; rather, each case examines particular facts to support the ultimate holding, and the writer had to derive the factors test in order to establish the analytical framework:

Factors the court should consider include: (1) whether the plaintiff initiated a Workers’ Compensation claim or passively accepted benefits; (2) whether the parties entered into a mediated settlement agreement; (3) the specific language of any agreement; (4) whether the employer accepted the claimant’s injuries; and (5) the actual parties to the agreement. See Jones v. Martin Elecs., Inc., 932 So. 2d 1100, 1105 (Fla. 2006); Hernandez v. United Contractors Corp., 766 So. 2d 1249, 1252–53 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2000); Vasquez v. Sorrells Grove Care, Inc., 962 So. 2d 411, 413–15 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2007); Petro Stopping Centers, L.P. v. Gall, 23 So. 3d 849, 852 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2009).[100]

Labeling the factors is a critical step in defining the analytical framework for a factors test. While articulating the rule reinforces knowledge already acquired, the process of labeling the categories requires more sophisticated reasoning than simpler rule structures demand. The power to create law also becomes more obvious to students as they begin to realize that they can construct categories either narrowly or broadly. A factors test is thus useful for reinforcing students’ foundations while incorporating increasingly challenging concepts.

The creation of a factors test is a powerful rhetorical strategy that lightens the cognitive load on the reader because it establishes an analytical framework to support the analysis.[101] The express articulation of the factors test informs the reader of the structure of the analysis that will follow, so the reader does not bear the burden of a heavy cognitive load in understanding the law governing the issues in the case.

Factors tests also increase opportunities for students to learn variations on the organizational paradigm. Most legal writing curricula begin by teaching students a symmetrical organization scheme where the entire rule is explained and then applied. This paradigm can be used with a factors test,[102] but it requires the reader to hold a lot of information in short-term memory, which can make the ultimate analysis more difficult to follow.

With a factors test, the symmetrical organization causes the legal standard to seem more abstract and detached, leading the decisionmaker to approach the decision from a more clinical, less personalized perspective. This organizational paradigm conveys to the reader that the issue is one of adding up all the factors, and the sheer number of factors in favor of one party will govern the outcome. The downside, however, is that there is little room to understand the quality of the evidence vis-à-vis a given factor, and it is hard for the reader to holistically comprehend the entirety of each factual scenario. In other words, the checklist approach interferes with the consideration of the totalities of the circumstances, or the entire universe of factors.

While organizing the analysis like a checklist has the benefit of creating the illusion that the bulk of evidence is in favor of one party or the other, it fails to cohesively explain the factors in a holistic way that emphasizes not only the number of factors, but also their relationship to each other and the quality of evidence necessary to tip the scale in favor of one party or the other. This structure can, therefore, be misleading, as most factors tests are not decided solely on the number of factors that weigh in favor of one party or the other; the quality of the evidence as well as the applicability and relationship of the factors in any given case are outcome-determinative.

The symmetrical paradigm is not necessarily the most sophisticated organizational option with more complicated rule structures because it tends to obfuscate nuances in the legal standard as it applies to a fact pattern.[103] In fact, from a historical perspective, many persuasive briefs that have been filed in the real world have not employed a symmetrical paradigm. Rather, they relied on an integrated paradigm wherein the rule explanation and application are much more intertwined, supplying information to the reader in a format that allows simplified processing of sophisticated and complex information through the creation of mental images or narratives.[104]

If the professor’s goal is to introduce students to variations on the traditional TREAC paradigm, such as an integrated paradigm, a factors-test problem is useful. The integrated paradigm is more adept at painting a complete picture for the reader, whereas the symmetrical paradigm is akin to handing the reader a few bottles of paint and asking the reader to imagine a landscape. With an integrated paradigm, the writer would draft illustrations using precedent so that the reader comprehends each factor both individually and relationally. By immediately applying the law to the facts after each illustration, the writer emphasizes the relationship of the factors to one another as a holistic legal standard, not discrete components operating in isolation. The symmetrical paradigm could be understood as a list of ingredients while the integrated paradigm is more like a fully prepared dish.

Under either the symmetrical or the integrated paradigms, however, the decisions students must make about organizational structure and synthesizing a cohesive rule of law are much more complex than those necessary for explaining and applying a simple declarative rule or a conjunctive test. The symmetrical model has the advantage of creating bulk and neutralizing emotional facts when each factor is explained one at a time and then applied like a checklist in the application section. The benefit of the integrated model is that it captures the relational interconnectivity of the factors test and provides a nuanced framework for deciding the issue.

If novice legal writers are required to analyze a factors test before they have gained proficiency in the basics taught through simpler tests, they will not have the foundation necessary to support this type of sophisticated reasoning. They will likely not know how to create an analytical framework by articulating a cogent rule of law because they will not have had experience identifying and explaining explicit rules. Inducing a rule that is not articulated explicitly in precedent is nearly impossible without first learning how to identify and explain rules that are clearly articulated in precedent. Additionally, students will not have a clear understanding of why articulating the rule is essential to crafting a strong analytical framework; they may not even comprehend what an analytical framework is, much less appreciate how necessary the framework is to supporting the legal argument.

With a factors test, students can also build on the rule-based, analogical, and counteranalogical reasoning that they have already learned by adding on policy-based reasoning. Factors tests often implicate policies because factors tests are designed to be flexible, not rigid like a conjunctive test. Policies guide the analysis to set the boundaries for how flexible the standard should be in a given circumstance.

For these reasons, factors tests tend to work well in the persuasive semester because the factually intensive analysis is conducive to creating balanced problems with strong arguments on both sides. Even in the real world, it is hard for lawyers to predict how a court will rule on a case where a factors test is involved. There are just too many moving parts for anyone to make a substantially certain prediction as to the outcome.

To summarize, the factors test typically demands a more sophisticated process of inductive reasoning to derive the rule than that required of simple declarative rules and conjunctive tests. It also requires more intensive analogical and counteranalogical reasoning in the application section. Factors tests are helpful for introducing policy-based reasoning because policies generally guide readers on how to consider the factors all together. Factors tests build on the foundational skills students acquire with the simple declarative rules and conjunctive tests, but they are not suitable for introducing foundational skills because they are too complex.

D. Developing Proficiency: Dealing with Disjunctive Tests

Disjunctive tests are one of the most complicated tests if both sides of the alternative are involved in the fact pattern. If only one alternative is involved in the fact pattern, it is possible to write a problem in a simpler form using one side of the disjunction for some of the foundational purposes previously identified in this Article. Consider for example a problem designed around the Florida statute for assault, which defines the offense as “an intentional, unlawful threat by word or act to do violence to the person of another, coupled with an apparent ability to do so, and doing some act which creates a well-founded fear in such other person that such violence is imminent.”[105] The only part that is disjunctive is “by word or act.” As suggested in Section III(B), supra, this statute could easily be used for a conjunctive test problem by simply creating a fact pattern that involves either a word or an act, but not both. On the other hand, if the goal is to create a more advanced problem and build on the conjunctive test concepts, the professor could have the students grapple with whether certain words and acts are, either separately or together, an intentional, unlawful threat, thereby creating a disjunctive test problem.

Like with factors tests, problems involving disjunctive tests require students to exercise sophisticated judgment in terms of adopting an organizational structure. Each alternative necessarily involves some other rule structure, and it is even possible to have one rule structure on one side with a different rule structure on the other. With a disjunctive test, addressing each alternative in turn is often the best way to organize the analysis. This organizational paradigm allows students to deal with one alternative at a time, which they are used to doing since they have already worked with other rule structures. The use of subheadings can help students stay organized and focused. Within each subheading students could choose to fully explain and apply each alternative, or students may choose to explain each alternative as a separate heading and then include a final heading applying the alternatives in a single section.

When both alternatives are at issue, students need to explain both standards in a way that persuades the court that one test is clearly controlling or superior to the other. Learning how to maintain candor to the court and fidelity to the law while persuasively arguing for one alternative over another is a complex task.

To summarize, the disjunctive test continues to build on the foundation students have established through the simpler tests.

E. Building Up Fluency: Balancing Tests and Defeasible Rules

Balancing tests build on concepts introduced through simpler tests by providing an opportunity to continue working on the same skills with an added layer of organizational complexity. Factors tests are frequently embedded on either side of a balancing test, so all of the concepts related to factors tests apply to balancing tests as well. One major difference, however, is that students will typically not be able to organize the analysis in the form of a checklist because balancing tests require a side-by-side examination rather than a linear or sequential series of conclusions. There is simply too much information to address it linearly because the reader would not be able to retain so much detail delivered in a clinical, abstract way. The linear format is not conducive to conveying complex information in a way that is understandable and helpful to the factfinder. That is why the balancing test is more complex than the other rule structures set out in this section.

Like factors tests, the balancing test often involves a holistic analysis of factors, but often different sets of factors apply to each side of the balance. In other words, there are likely at least two factors tests embedded in any balancing test. Synthesizing and organizing two factors tests at the same time while explaining their relationship to each other requires students to exercise even more judgment than they had to exercise with the factors test. With the balancing test, the factors on each side of the balance are not only interconnected within each cluster, but they also together have a relationship with the cluster on the other side of the balance. All of these relationships influence the outcome. Now, instead of holding one cluster of factors at a time, students must hold multiple clusters at once, all while continuing to manage the ever-shifting relations amongst the components.

Balancing tests are often derived from caselaw, though a balancing test may be set up in a statute or constitutional provision.[106] Balancing tests often involve constitutional questions and implicate competing policies or special interests. Especially when derived from caselaw, the structure of the balancing test can be malleable in terms of setting up the analytical framework for the argument. For example, balancing tests can frequently be worded as a defeasible rule in order to convey a different sense of judicial power associated with the test. In the example below,[107] Rule 1 is structured as a balancing test while Rule 2 is structured as a defeasible rule.

-

The state’s right to forcibly medicate the defendant to restore her competency to stand trial must be weighed against the individual’s right to privacy, which encompasses the right to refuse medical treatment.

-

The Fourth Amendment right to privacy protects an individual from being forcibly medicated to restore competency to stand trial unless the state has an important interest in prosecuting a serious crime.

Both rules are accurate, but the former suggests the parties stand on equal footing while the latter conveys a broad protection for the individual with a narrow exception for state action. The very structure of the rule subtly persuades the decisionmaker about how much power the court has to forcibly medicate the defendant for the purpose of restoring competency to stand trial. Balancing tests are effective tools for teaching students more advanced persuasive and rhetorical strategies, and they can be especially useful for writing as resistance pedagogies[108] because they allow students more freedom in how they define the issues, describe the parties, and organize the analysis.

To summarize, balancing and defeasible tests can be interchangeable rule structures that provide students the opportunity to learn malleability of rule structures for persuasive appeal. These rule structures build on those concepts already introduced with simpler tests, essentially scaffolding the complexity in a way that the brain can process for long-term learning.

F. A Summary

The following table summarizes the connection between rule structure and pedagogical goals, and it also includes suggestions for where a professor might identify examples of rule structures around which to build problems:

Conclusion

Centering the pedagogical goals and student learning experience requires professors to think intentionally about problem design. Learning theory and cognitive science unequivocally inform that students learn best when new information is relatable to prior experiences. As such, it only makes sense to begin simple and then scaffold the learning experience to the more complex.

This Article offers a new, particularized focus on rule structure for the intentional integration of learning outcomes into specific problems. When designing problems, best practices demand that professors first consider the pedagogical goals. Thereafter, selection of a corresponding rule structure lends itself to identifying a manageable rule and body of legal authority around which to build the problem. To some extent there is a relationship between the complexity of rule structure and complexity of the area of law, as reflected in the table in Section III(F), but from the pedagogical perspective, the rule structure provides a more manageable way to map problem design to desired learning outcomes. Thus, especially for novice professors or even experienced professors who are seeking a more deliberate method for problem creation, rule structure provides a grounding infrastructure to ensure desired learning outcomes are achieved through the problem.

Generally, the only major change from year to year in a legal writing course is the problem, or problems, assigned to the students. Most professors adopt a textbook and stick with it, and they tend to approach class lectures in similar ways year after year. The problem, though, operates like a separate text for the course, and, for most professors, it consistently changes from year to year for a variety of reasons, including, but not limited to, reducing the temptation for students to plagiarize or otherwise cheat on assignments. See generally Lorraine Bannai, Anne Enquist, Judith Maier & Susan McClellan, Sailing Through Designing Memo Assignments, 5 Legal Writing 193, 194 (1999); Rita Barnett-Rose, Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle: How Using “Recycled” Simulations in an LRW Course Benefits Students, LRW Professors, and the Relevant Global Community Special Issue: Articles on Legal Research and Writing, 38 U. Dayton L. Rev. 1, 2 (2012); Jan M. Levine, Designing Assignments for Teaching Legal Analysis, Research and Writing, 3 Persps.: Teaching Legal Res. & Writing 58 (1995); Ellie Margolis & Susan L. DeJarnatt, Moving beyond Product to Process: Building a Better LRW Program, 46 Santa Clara L. Rev. 93, 131 (2005).

Thank you to Dean Anne Mullins for coining the phrase “integrated learning experience” after reading an early draft of this article.

Recycling problems can increase issues such as plagiarism and cheating because current students may find it easier to obtain work submitted in prior years and either submit it as their own or modify it to become their own work. Either way, using a new problem helps to maintain a more level playing field in the classroom and reduces opportunities to cheat or plagiarize.

See generally Bannai, Enquist, Maier & McClellan, supra note 1; Leonore F. Carpenter & Bonny Tavares, Learning by Accident, Learning by Design: Thinking About the Production of Substantive Knowledge in the LRW Classroom, 88 UMKC L. Rev. 39 (2019); Gail Anne Kintzer, Maureen Straub Kordesh & C. Ann Sheehan, Rule Based Legal Writing Problems: A Pedagogical Approach, 3 Legal Writing 143 (1997); Grace Tonner & Diana Pratt, Selecting and Designing Effective Legal Writing Problems, 3 Legal Writing 163 (1997). The Bannai et al., article does lay out a process for problem design, but it only provides abstract characteristics that professors should keep in mind without guiding them on why these are important, how they influence decisions, and what ultimately influences the final design of the problem. See Bannai, Enquist, Maier & McClellan, supra note 1. Kintzer et al., share their experiences with very specific problems using certain legal doctrines, but they do not explain how they created the problems. See Kintzer, Kordesh & Sheehan, supra.

Supra note 4; infra notes 12–13.

“In an emerging area like legal writing, even those who teach legal writing may not share a common language.” Terrill Pollman, Building a Tower of Babel or Building a Discipline—Talking about Legal Writing, 85 Marquette L. Rev. 887, 889 (2002).

As used here, jargon means “the language of a profession . . . created specifically for use in the workplace.” Id. at 888 (internal quotes omitted).

This non-exhaustive list identifies just some of the legal writing texts currently on the market: Jill Barton & Rachel H. Smith, The Handbook for the New Legal Writer (3d ed. 2023); Mary Beth Beazley & Monte Smith, Legal Writing for Legal Readers: Predictive Writing for First Year Students (3d ed. 2022); Robin Boyle-Laisure, Christine Coughlin & Sandy Patrick, Becoming a Legal Writer: A Workbook with Explanations to Develop Objective Legal Analysis and Writing Skills (2019); Charles R. Calleros & Kimberly Y.W. Holst, Legal Method and Writing (9th ed. 2022); Alexa Z. Chew & Katie Rose Guest Pryal, The Complete Legal Writer (2d ed. 2020); Linda H. Edwards & Samantha A. Moppett, Legal Writing and Analysis (6th ed. 2023); Linda Edwards & Samantha A. Moppett, Legal Writing; Process, Analysis, and Organization (8th ed. 2022); Cassandra L. Hill, D’Andra Millsap Shu & Katherine T. Vukadin, The Legal Memo: 50 Exercises for Mastery: Practice for the New Legal Writer (2021); Teri A. McMurtry-Chubb, Legal Writing in the Disciplines: A Guide to Legal Writing Mastery (2012); Richard K. Neumann, Jr., Ellie Margolis & Kathryn M. Stanchi, Legal Reasoning and Legal Writing (9th ed. 2021); Richard K. Neumann, Jr., Sheila Simon & Suzianne D. Painter-Thorne, Legal Writing (5th ed. 2023); Laurel Currie Oates, Anne M. Enquist & Jeremy Francis, The Legal Writing Handbook: Analysis, Research, and Writing (8th ed. 2021); Joan Malmud Rocklin, Robert B. Rocklin, Christine Coughlin & Sandy Patrick, An Advocate Persuades (2d ed. 2022).

See infra Section III.