In recent years, legal writing scholars and practitioners have looked beyond the confines of traditional scholarship and practice to show how understanding other artistic forms of communication can inform and enhance legal writing.[1] In this vein, I argue that persuasive legal writers will benefit from understanding and applying photographic composition principles to their writings.

Specifically, this article explores two principles of composition employed by twentieth century landscape photographer Ansel Adams. I argue that one of those principles should apply to legal writing introductions, and the other principle should apply to legal writing conclusions. Adams stated these photographic composition principles as follows:

A good photograph is knowing where to stand.[2]

A great photograph is one that fully expresses what one feels, in the deepest sense, about what is being photographed . . .[3]

Applying these principles to legal writing, the legal writer in an introduction should tell the reader where the writer stands on the issue in the case. In the conclusion of the same brief, the legal writer should tell the reader how the writer feels about the issue in the case. The corollary to this argument is that the traditional legal writing roadmap introduction (tell the reader what you are going to say) and the traditional legal writing summary conclusion (tell the reader what you already said) should be omitted.

I. Ansel Adams

Ansel Adams looms large as the twentieth century’s greatest landscape photographer. Born in 1902, Adams “was a rare and wonderful man, an artist with a unified vision, and intellect with a multiplicity of interests.”[4] At sixteen, Adams traveled to Yosemite and began making photographs; he made them the rest of his life. Adams’s iconic black and white images are “elegant, handsomely composed, technically flawless photographs of magnificent natural landscapes.”[5]

The citation to Adams’s 1980 Presidential Medal of Freedom reads “[a]t one with the power of the American landscape, and renowned for the patient skill and timeless beauty of his work, photographer Ansel Adams has been visionary in his efforts to preserve this country’s wild and scenic areas, both on film and on earth.”[6] President Carter chose Adams to make the official president’s photograph—the only photograph in the National Portrait Gallery.[7] Since his death in 1984, Adams’s reputation has continued to grow, as demonstrated by scores of museum exhibitions[8] and books.[9]

At the heart of Adams’s craft lies a consistent philosophy of what it takes to compose a great image. This article explores two principles of Adams’s philosophy for guidance on how to render persuasive legal writing just a little better.

II. It’s All Communication: The Overlap of Photographic Composition and Writing Composition

Examples of the intersection of various arts and writing are legion. Rudyard Kipling, Henry Miller, and many others were also painters.[10] Warhol, Picasso, and Dali, painters all, were also writers.[11] Jack London[12] and Eudora Welty,[13] great writers, were also accomplished photographers. Novelist Donald Friedman profiles hundreds of great writers, including 13 Nobel laureates, who were also artists in other ways in The Writer’s Brush: Paintings, Drawings, and Sculpture by Writers. Quoting W.B. Yeats from “Art and Ideas,” Friedman concludes that “nor had we better warrant to separate one art from another.”[14]

Photography is an art. As with other arts, photography shares much in common with writing. Both art forms rely on composition to be effective in influencing the audience as the photographer/writer intends. Understanding this truism is central to understanding why Ansel Adams’s two principles matter for persuasive legal writing.

Ansel Adams’s photography—all photography for that matter—is an artistic form of non-verbal communication that puts a three-dimensional object on a two-dimensional surface—paper or screen—to convince the viewer of the photographer’s message.[15] Persuasive legal writing, whether a motion, brief, or other document, seeks to convince reader(s) of the writer’s message, which in the case of an attorney usually means the writer’s client(s) should prevail.[16]

Photography and persuasive writing are not so different. As British novelist Arnold Bennett noted, “[g]raphic art cannot be totally separated from literary art, nor vice versa. They encroach on each other.”[17] Good photographs are viewer focused. Lesser photographs are photographer focused.[18] The same dichotomy applies to legal writing. Effective legal writing is reader focused. Yet, too often legal writers produce text like they did as high school or college students— writing that is self-expressive, or in other words, writer focused.[19]

Photographs, as well as other works of graphic art, that are viewer focused don’t just happen—artists compose those works to increase the likelihood that the viewer will be impacted by the image in the way the artists intend. This intentionality is called “composition,” from the Latin componere (translated as “to put together”).[20] Composition means the arrangement or placement of elements within a work.[21]

Composition applies not only to photography, music, and other arts but to writing as well.[22] The author “composing” the novel or legal brief, the painter composing the oil on canvas, and the songwriter composing the ballad, each guided by principles of composition, put together the elements of their work in a manner of their choosing to achieve their intended purpose for their intended audience.[23] In music, composition affects how the listener experiences the work.[24] In visual arts, composition operates to direct the viewer’s eyes across the work.[25] In writing, composition guides the reader as to where to place weight, as well as influences the reader’s attitude towards the writing.[26] All composition, regardless of the medium, focuses the audience on how the creator intends that audience to experience the work.

Turning specifically to how viewers “read a photograph,” the principles of photo composition take advantage of how the viewer’s eye moves across an image and how the viewer’s brain then creates the impression so that the viewer experiences what the photographer intends.[27] In his classic book, The Art of Photography, Bruce Barnbaum writes, “Good composition is the artist’s way of directing the viewer’s vision in a planned de-randomized fashion.”[28] He continues, “[W]hen a photograph is well composed, viewers first see the elements that the artist wants them to see most prominently and remember the longest. . . . With good composition, the artist leads viewers through the photograph in a controlled manner.”[29] Similarly, rhetorical (persuasive) writing is about the audience reading the text (with their eyes and brain) to get each reader to agree with the author’s position.[30]

There are scores of books and articles on photographic composition[31] theory and practice. So too the shelves of law libraries run for yards with the material aimed at making lawyers (and law students) more effective writers.[32] This is so because, as touched on above, composition is composition whether visual or textual, and it is central to the endeavor.

For example, Adams credited his mastery of piano as key to his proficiency as a photographer.[33] Photographers find inspiration not only in painting and other visual arts, but in music, literature, and poetry.[34] Composition in all art forms is made more effective by an artist’s understanding of composition in forms other than their own.[35] Thus, understanding composition in the art of photography informs composition in the art of persuasive legal writing.

The recognition of the overlap between the visual arts and writing is not new. Plutarch and Horace compared poems to pictures.[36] Ezra Pound wrote “[t]he image is more than an idea. It is a vortex or cluster of fused ideas and is endowed with energy.”[37] And today, visual rhetoric is the study of “anything from the use of images as argument, to the arrangement of elements on a page for rhetorical effect, to the use of typography (fonts), and more.”[38] A photograph, as visual text, “can advocate or state a position, articulate concepts, and explain difficult procedures. [It] can also entice viewers to respond to messages, acting or thinking in a particular way.”[39] Composition is composition is composition.

And yet, there is little scholarship dealing directly with the intersection of photo composition and writing, much less photo composition and legal writing. Some authority does exist, however. For example, in 1998, Professor Vincent Miholic published a thoughtful article observing that “the basic processes and creative act of photography parallel those of writing” and arguing that utilizing photography principles will help college students to write better detail.[40]

Similarly, Professor Eric H. Hobson argues that writing benefits from instruction in perspectives other than that of the production of written texts. [41] Quoting R. Baird Shuman and Denny Wolfe, Hobson notes the importance of viewing writing “composition” from other composition perspectives:

Our point here is that writing is like all the other arts in this regard: all are composing activities and therefore require invention. Just as composition in speaking and writing has to do with ordering words, so composition in music has to do with ordering sound and drawing or painting has to do with ordering objects in space, and so on. All forms of composition assist in the process of clarifying and ordering thought and feeling, in creating and understanding concepts-in short, in learning.[42]

The final illustrative work is from Professor Barbara P. Blumenfeld, who explains how determining a theme, focusing attention on that theme, and simplifying (all of which are photo composition principles), apply to legal writing.[43] In an email to the author, Blumenfeld explained:

I used to use photography and ideas/examples from photography regularly in my legal writing classes—especially those on persuasive writing, . . . It always seemed that I could use photos to convey writing concepts and because of the immediacy of a photo the students were more able to grasp—to actually see—the writing concept that I was trying to convey to them.[44]

In this article, I seek to expand on this scholarship that attempts to broaden lawyers’ understanding of “composition” by introducing the basics of photo composition theory and how the architecture of the viewer’s brain functions to distinguish a good photo from a not good one. Second, I turn to the purpose and criticism of persuasive legal writing by focusing on the two least examined sections of a persuasive work: the introduction and the conclusion. Third, I look to Ansel Adams and two of his principles of photo composition to point out a way to craft more effective introductions and conclusions. The article concludes that the domains of photo composition and persuasive legal writing are more similar than they may first appear.

Looking for inspiration in other forms of expression, whether music, or painting, or even dance, and specifically photography here, will help lawyers write better, and legal writers should look beyond traditional sources for additional guidance to improve their writing.

III. Some Background on the Principles of Photo Composition: What Makes a Good Photograph a Good Photograph

While this article only focuses on two photo composition principles, some background on composition generally is in order. With a broader understanding of what it takes to make a good photo generally, the importance of Adams’s two principles that are the subject of this article come into better focus. The congruence between the visual text and the written text explains why composition principles in one art form inform the composition principles in other art forms. Just as Ansel Adams’s training as a pianist enhanced his photography, so too will an understanding of some of the principles of photo composition make legal writers a little better at the craft.

A good photograph is not “taken.” Rather, a good photograph is “made.”[45] This distinction recognizes the photographer as the master of the image. Photographers make choices—from before they pick up the camera until the click, and to a degree even beyond in developing the image in the dark room (old school) or using software to adjust the image on a computer (new school). Lithuanian photographer and author Romanas Naryškin explains how a photographer’s composition choices matter: “A good composition can help make a masterpiece even out of the dullest objects and subjects in the plainest of environments. On the other hand, a bad composition can ruin a photograph completely, despite how interesting the subject may be.”[46]

While Aristotle certainly did not own a Nikon, his definition of rhetoric, as “discovering in any particular case all of the available means of persuasion,”[47] encapsulates the essence of photo composition. The authors of a principal text on photo composition explain that “the composition of a photograph is the means a photographer has at his disposal to direct another person towards or through the idea that motivated the photograph in the first place. In that sense, composition manipulates.”[48] The authors conclude that composition “extends the influence of the photographer, enabling him to influence the viewer physically, emotionally, and intellectually.”[49] In other words, photo composition is rhetoric![50]

There are scores of principles of this rhetoric—of photo composition—most of which are shared generally with visual arts.[51] The more important principles of photo composition include:

Edward Weston, the famous twentieth century landscape photographer, summed up the function of all photo composition guidelines when he observed that “[c]omposition is the strongest way of seeing.”[56]

Photo composition principles function effectively based on the complex and counter-intuitive way humans perceive and process images. In the 1960s, psychologist A.L. Yarbus demonstrated that people randomly scan “up and down, side to side, picking out bits and pieces here and there, and sending these tidbits back to our brain at a furious pace” where the brain “puts it all together, like a mosaic or jigsaw puzzle.”[57] This ultra-fast “pause and jump,” a physiological process called saccads, results from the fact that only the small central part of the retina, the fovea, has high resolution that captures the pieces of the scene. The brain then puts those pieces together to record the total view in short term memory.[58]

What this physiology of the eye and brain means is that what we perceive as a single “ooh ahh” moment when we see, for example, a Grand Canyon sunrise or a Monet water lily painting, is not a moment at all. Rather, our eyes see distinct “small chunks” of the scene sharply at one time, and then our brains piece those chunks together to form a complete picture that we interpret as in the moment.[59] Photo composition principles work by using this eye movement across the image to engage the viewer and to keep them engaged. The photographer needs to understand how the brain, eye, and memory work together in order to make a photograph, not just take a photograph.

Reading works much the same way. As Professor Douglas convincingly argues in The Reader’s Brain: How Neuroscience Can Make You a Better Writer, the science of more effective writing is based on better understanding the science of how we read.[60] Douglas shows how the visual, auditory, and speech centers of our brains are physiologically interconnected.[61] Reading is a new human skill. With our species only reading for a flicker of evolutionary time, it is no surprise that reading is only made “possible from connections among areas of the brain enabling us to translate visual marks into speech, areas enabling us to speak, and areas that convert torrents of sound into syntax.”[62]

The complex physiological process of reading happens in three steps. First, readers use grammar to recognize individual words—this is called lexical processing. In the second step, called “syntactic processing,” the reader uses syntax to make sense of the word using surrounding words to anticipate how the sentence will play out. Finally, inferential processing, based on schema “we’ve acquired to make sense of the world,” is used when the combination of the first and second fail to make sense of a text. Simply put, we first comprehend, then assimilate, and finally, infer to arrive at meaning.[63] These reading processes are the same processes that operate in photo composition because visual language operates as just that, a language. As Grill and Scanlon explain, “in the language of visual arts, grammar and syntax are called composition.”[64]

In sum, we should not separate photo composition from writing composition. Both rely on composition principles rooted in brain science in order that the audience better understands the sender’s intended message. Legal writers’ message is to convince the reader the lawyer should prevail, and to that we now turn.

IV. Applying Adams’s Photo Composition Principles to Persuasive Legal Writing

A. Purpose and Criticism of Persuasive Legal Writing with Focus on the Introduction and the Conclusion

The function of legal writing in general, and persuasive legal writing in particular, is to get the reader to agree with the writer’s position. It is reader-focused writing.[65] Types of persuasive legal documents include demand and settlement letters, complaints, answers, motions, trial briefs, and appellate briefs.

Such persuasive legal writing needs improvement according to practitioners,[66] judges,[67] and just about everyone else with an opinion.[68] To be good, legal writing should be precise, concise, simple, clear,[69] and engaging.[70] Yet legal writing, according to the critics, is “too wordy, too laden with jargon, and too boring,”[71] and even suffers from poor grammar.[72] The complaints about legal writing go back at least a century.[73] Critics cite many causes, including:

-

Economic reasons “like lawyers creating complicated documents to justify fees, prove their importance, or create a need for their services”;

-

Psychological barriers “like resistance to change, reliance on templates and tradition, and pressure to conform with the past”;

-

Lawyers who “cannot see the problems in their own writing”; and

-

“Pragmatic barriers like time constraints, the costs of change and training, and the lack of sufficient training and writing practice.”[74]

My aim is neither to address (much less try to remedy) all these ills nor to interrogate their cause(s). Rather, I focus only on the introduction and conclusion elements of briefs and other persuasive legal documents by offering an untraditional approach to drafting those elements in order to improve their impact. Despite “a truth universally acknowledged [that the] beginning and end of any piece of writing make the greatest impression on readers,”[75] introductions and conclusions tend to be given short shrift in the writing process.[76] This article seeks to change that and to change the way lawyers conceptualize and draft those document elements.

Before diving in, a final prefatory note: just as photographers consider rules of composition to be guidelines, so too is the recommendation to apply Adams’s two composition principles to drafting legal writing introductions and conclusions. As Professor Ian Gallacher aptly notes when it comes to writing rules, “there are no rules . . . just suggestions.”[77] It is your writing, and you make the final decision on what to write and how to write it.

B. Introductions: Knowing Where to Stand

1. The Traditional Legal Writing Introduction

Although there are some well-written and thoughtful resources published on how to write an effective introduction[78] and an effective conclusion,[79] these components of persuasive documents fairly frequently fall victim to the oft-repeated advice for writers (and all presenters) to “tell 'em what you’re gonna tell 'em, tell 'em, and then tell 'em what you’ve told 'em.”[80] Some claim the source of this “tripartite template” is preachers[81] while others cite Aristotle.[82] Whatever its genesis, this advice is de rigueur for persuasive writing instruction at every level.[83] Let’s turn first to introductions.

Novice persuasive writers in middle school[84] and high school[85] learn the five-paragraph theme[86] as the template for persuasive writing. As part of that, they are taught that roadmaps are a key part of their introduction to their essay. Students are commanded to tell the reader what they are going to write about and provide a clear (often enumerated) roadmap.

College writing is much the same. The introduction serves to set out the thesis, the claim, and then the organization of the paper, the roadmap.[87] Many universities maintain an Online Writing Lab (OWL) as an extension of their in-person writing centers. Purdue University’s OWL is popular, with hundreds of millions of page-views every year.[88] This “go-to” resource recommends that writers use the following:

The preacher’s maxim is one of the most effective formulas to follow for argument papers:

Tell what you’re going to tell them (introduction).

Tell them (body).

Tell them what you told them (conclusion).[89]

And yes, lawyers, too, are advised to rely on this formula[90] called the “three principles of any good presentation.”[91] In their briefs, lawyers are told they should include a “good roadmap paragraph” to help the “reader understand the structure of the argument.”[92] Just like back in high school, “this elemental theory of argumentation is: ‘Tell them what you are going to tell them; tell them; then tell them what you’ve told them.’”[93]

A few authorities, besides me, also argue that introductions should not include roadmaps. For example, Professor Timothy P. Terrell and lawyer Stephen V. Armstrong advocate for “ambitious introductions” that “capture and impress the reader” and quickly provide reassurance to the reader of “what’s your point.”[94] Also rejecting the tripartite template, Professor Amy Bitterman argues that introductory statements should include a theme that drives the reader to agree with you on “an instinctual level.”[95] But these authorities are the exception.

Focusing on legal writing specifically, the standard advice to lawyers is that an introduction should indeed not just preview the argument but should provide the roadmap. For example, Georgetown University Law School’s Writing Center’s white paper entitled Introductions and Conclusions for Scholarly Papers suggests that an effective introduction should “hook” the reader, “highlight the thesis statement that guides the paper” and lay “out a roadmap for the reader to show her how the paper will prove its thesis.”[96] One legal writing textbook recommends that the introduction “summarize the essentials that you will discuss in the ensuing material.”[97] Again, an introduction that serves as preview includes the roadmap for the brief or memo.

Practicing lawyers also recommend a roadmap introduction. One lawyer terms this a “substantive introduction” and explains that it is “like a movie preview; it tells the reader in short form what the case is about and what arguments will be developed in the body of the brief. Like a movie preview, it gives the reader the main characters and enough of the plot to pique his or her interest.”[98] Another lawyer puts it this way: “Think of your introduction more as an executive summary. Don’t just introduce what’s to come; instead, summarize everything that follows. . . . Make the introduction self-contained—that is, summarize all the best parts of what’s to come later in the brief—so that a judge doesn’t have to read any further.”[99] There is even an entire article dedicated to roadmap introductions that concludes:

[r]oadmap paragraphs help the reader understand written legal arguments. They give a preview of what’s to come later in the argument and provide a framework of conclusions, law and facts in which to organize the remaining details of the argument. Thus, because they are more easily understood, the arguments are more persuasive.[100]

Again, the advice is for an introduction to lay out for the reader the road ahead. Such advice is wrong.

2. In Most Persuasive Legal Documents, Traditional Introduction with Roadmap Serves Little Purpose as Sophisticated Readers Already Know the Topics Addressed

First, before digging into the argument, some clarification is in order. Introductions are crucial. They invite the reader into the text. A preview is typical in an introduction and foreshadows what the reader should expect. Adams’s principle of “knowing where to stand” is about “previewing” the photo he is about to make. But a preview does not mean “tell them what you are going to tell them”—that is a roadmap. A roadmap shows the driver where the driver is going to drive. A roadmap introduction shows the reader what they are going to read.

In contrast with roadmaps, which enumerate and detail, previews invite. A wedding invitation is a preview that gives the guest some details to get the invitee ready for the event. But a wedding invitation does not “show 'em” what is going to be said at the ceremony, or what is for dinner, the wine to be served, or the playlist the band will bang out. No need for that. The invitation provides the pathway into the experience. That is what a legal writing introduction should do.

United States Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts pointed out the distinction between the roadmap introduction and a more effective preview “introduction” that focuses the reader on where the writer stands. “I think an introduction is different than a summary.”[101] A proper introduction is “almost never . . . ‘In part one I’m going to say this, and in part two I’m going to say this, and in part three I’m going to say this.’”[102] An effective introduction, Chief Justice Roberts noted, shows where the advocate stands. “It’s more, ‘This story is about what happened when this, this, and this, and the court below said this, and that’s wrong because of this and this.’ And then go into it.”[103]

Chief Justice Roberts is correct because a roadmap in an introduction to a legal brief serves no purpose for the intended audience. The advice to “tell 'em what you’re going to say, say it, and then tell 'em what you said” merely rephrases the advice that you “hammer things home to your audience and help them remember.”[104] But sometimes a hammer is the wrong tool. For one thing, a roadmap in an introduction can be viewed by the audience as “maddeningly patronizing,” particularly in a shorter writing.[105] As one critic of such introductions for presentations puts it: “It’s also quite possibly the biggest load of nonsense I have ever come across and the one piece of advice that, if followed, is guaranteed to make your next presentation a boring one. [This] simple format . . . is great if you are a six-year-old doing show and tell at your school.”[106] The same critique applies to the use of a roadmap introduction in persuasive legal writing.

Another criticism of roadmaps in introductions is that this kind of “tracking” is “basically [a] plodding method.”[107] Professor Peter Elbow, an influential composition scholar, notes that roadmap introductions lack thought,[108] and Richard Posner criticizes such introductions as lacking subtlety and finesse.[109]

Perhaps the most apt criticism of employing a roadmap introduction in a persuasive legal document is that such a device wastes the reader’s time. Attorneys should strive to write simply and concisely.[110] Judges tell us briefs should be brief.[111] Even so, judges, like lawyers, are guilty of bloated writing.[112] Cognitive science research shows that lack of concision creates confusion.[113] A step towards more concise writing would be to cast aside roadmaps as part of any introduction except in the rarest of cases because they state the obvious and waste a reader’s time.[114]

To save himself time, Justice Scalia made a practice of not reading the Summary of Argument sections required for Supreme Court briefs. “I usually don’t read it because I’m going to read the brief” he told the interviewer.[115] He continued, “I don’t know why it’s there. Maybe for those judges who don’t intend to read the brief.”[116] And he laughed. The superfluousness that a roadmap provides in most writing situations serves as the strongest reason for staying away from including it as the introduction in a persuasive legal document.

Despite this criticism, some have cited scientific evidence to support utilizing a roadmap introduction in legal writings. As Professors Catherine J. Cameron and Lance N. Long argue in The Science Behind the Art of Legal Writing,[117] road mapping introductions are a type of “advance organizer” that serve to “assist legal readers in learning and retaining information the legal writer wants to convey.”[118] The grounding for this claim is the pioneering work of cognitive researcher David Ausubel.[119]

Ausubel’s studies establish that roadmaps can help readers to comprehend better the text that follows.[120] Road mapping is just the first third of the Preacher’s tripartite template—“tell 'em what you are going to tell 'em.” Professors Cameron and Long discuss these studies, which originate mostly from the field of education, and note that “legal writers are very much like teachers” who teach legal readers.[121] Therefore, they contend “it correlates that using the Ausebelian principles of advance organizers will assist legal readers in learning and retaining the information the legal writer wants to convey.”[122]

While advance organizers do benefit new legal learners like law students,[123] judges and lawyer are not students.[124] And judges and lawyers are the primary readers of briefs, memoranda, and other persuasive legal documents. In this reality of the audience lies a flaw in Cameron’s and Long’s argument.[125] To be sure, advance organizers can assist some readers to understand what is to come, but that fact does not translate into the wisdom of uniformly using a roadmap as part of the introduction in all persuasive legal texts.

First, judges and other lawyers who read briefs, memos, or letters already have a good idea of what the case is about and the arguments, too. Advance organizers should be used “where the learner (reader) does not normally possess or use an assimilation context for incorporating the new material.”[126] Advance organizers can, therefore, be useful to a learner (reader) when the material appears unorganized or “unfamiliar or when the learner lacks the related knowledge or ability to comprehend the knowledge.”[127] Judges and lawyers do not generally fall into this category. By contrast, first-year law students are novice learners and likely will benefit from the use of advance organizers.[128]

Second, if the judge or lawyer is unfamiliar with what is being presented before they pick up the document, the subject headings, issue presented section, table of contents, and other similar advance organizers will aid them in comprehending a writer’s argument.[129] A roadmap is little needed when there are already signposts every step of the journey. Too many advance organizers become like too many road signs, turning the easily navigable journey into confusion and aggravation.

Finally, and it’s a small point, many courts impose page limits on submissions. If one succumbs to including a roadmap section, valuable pages will be taken from the argument section where page use is most needed.

In sum, does a roadmap in an introduction aid the judge or the lawyer who knows why you are writing the brief or the memorandum and is presumably familiar with the law at issue? Probably not. In place of the roadmap introduction, Ansel Adams’s composition advice to know where to stand, explained below, offers an alternative to the rote roadmap introduction, which may be better suited to persuading the judge or lawyer to agree with the writer’s argument.

3. The First Step to Photo Composition: Knowing Where to Stand

Ansel Adams counseled that “[a] good photograph is knowing where to stand.”[130] Echoing this sentiment, one scholar wrote “[a] photograph is necessarily taken from a certain angle, with a certain distance, in a certain light, with a certain lens. Such conditions contribute in creating meaning—and thus the argumentative dimensions—of the picture.”[131] For the photographer, where to stand matters because it directs all that comes after. How to then “compose” the elements that are in the frame? What to focus on, what to blur away, and so on. The relative size of objects, and shapes, light, and shadow are all governed by where the photographer chooses to stand. As shown below, the same holds true for the lawyer writing a persuasive document.

Captured in the phrase “where to stand” are three interconnected ideas that make up the initial steps to making a compelling image.

Point of view: Where do I stand? asks the photographer. The position of the photographer determines the angle or point of view—from low or high, right side or left side, far away or near. This is first.

Frame: Where the photographer stands impacts what winds up in the image, but the photographer also chooses where to point the camera and whether to zoom in or zoom out. What is outside the viewfinder—the frame—does not exist. This is second.

Perspective: This is the photographer’s “take” on the image she or he is making. Is it dramatic, sublime, haunting, cheerful, striking, magnetic, splendid, powerful, thought-provoking, etc.? Where the photographer stands and points the lens dictates the perspective, the “appearance of objects in space, and their relationship to each other and the viewer.”[132] The photographer conveys his or her perspective with the frame he or she chooses.

These three elements fall under the broad category of what Adams called “visualization”—the ability to reason out how the final print will look and control that result by taking action before the exposure is made.[133]

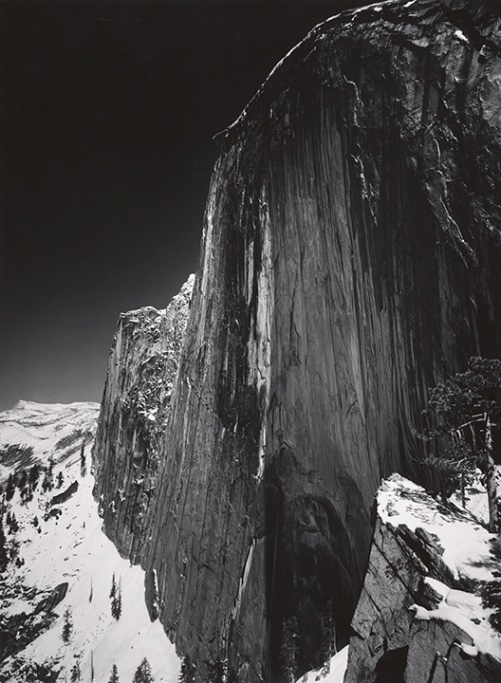

Adams arrived at the epiphany of visualization in the early months of 1927. As Adams later explained, to make an image of Half Dome he climbed to the location that he felt would give an unparalleled “view of Yosemite Valley’s most spectacular earth gesture.'”[134] This “place to stand” was called the “Diving Board,” a large rock that “jets out over the Yosemite Valley, four thousand feet below the western face, providing the perfect view of Half Dome.”[135]

Adams considered the making of this photograph “one of the most exciting moments in [his] photographic career.”[136] He called the image Monolith, The Face of Half Dome.[137]

In this image, Adams’s point of view, frame, and perspective are clear. His point of view is slightly straight on and at a distance. As Adams explains it, he and four friends including his wife, made the cold climb and “ahead of us rose the long, continuous rising slope of Half Dome.” They climbed another 1,500 feet for the perfect point of view.[138] This image was only possible from that specific point of view.

Adams framed the image (chose what to keep in and what to keep out) by filling the frame with mostly Half Dome, rather than zooming in or zooming out.[139] He positioned the monolith to the right, encircled on the bottom by a collar of snow, and chose the upper-left quarter to be contrasting black sky. These three elements comprise the photograph with much of Half Dome out of the frame, as well as leaving out most of the adjacent mountain. The framing focuses the viewers to look from bottom to top and right to left as their eyes scan the image.

Finally, Adams’s perspective—his “take” on the subject matter—is clear: unapologetic reverence. This “take” is conveyed by the chosen frame. As Adams explained, “I saw the photograph as a brooding form, with deep shadows and a distant sharp white peak against a dark sky.”[140] This image is one of Adams’s most important works, a label he, himself, attached to the image as well.[141]

4. Knowing Where to Stand: Point of View, Frame, and Perspective Offer an Alternative Introduction Form for Legal Writing

As explained at length above, in legal writing, roadmap introductions waste paper (or computer memory) and, most importantly, waste the reader’s time. Such tedium should be avoided. Instead, the introduction should make clear where you stand on the matter in dispute. In doing this, you should let the reader know your chosen point of view, frame, and perspective. This will draw your reader into the text rather than bore them.

Bryan A. Garner, in his treatise The Winning Brief, makes the point that a persuasive legal document must convey the “big picture” and do so early in the document.[142] His advice is cogent and compelling:

Every brief should make its primary point within 90 seconds. But probably only 1% of American briefs actually succeed on this score. The ones that do are spectacular to read: on the first page the judge gets your stand on the basic question, your answer to that question, and the reasons for that answer.[143]

The judge should “get your stand” from the outset. Although he does not cite Ansel Adams, Garner embraces Adams’s first principle of good photography for legal writing—knowing where to stand. As another authority put it, your introduction “better pack a wallop [because in] it, we introduce the court to our case: to our client and to our theory. And, we tell the court, in the simplest terms possible, exactly what it must know to rule in our favor.”[144]

“Knowing where to stand” is what sets the frame. Framing suggests to the reader a perspective—the perspective that the author wants the reader to embrace. Suggesting to the reader how to view the dispute is critical to the ultimate task of persuading the reader to agree with you. Offering advice about academic legal writing, Professor Eugene Volokh argues that frames are important from the outset because they “focus” the reader’s attention where the writer wants it focused.[145] In his words, a frame at the outset “puts the reader in the right mindset to absorb and agree with your point. Write with this in mind.”[146]

Framing this way drives the intended audience’s perspective on the dispute. As Professor Robert M. Entman notes regarding all written communication:

Framing essentially involves selection and salience. To frame is to select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation for the item described.[147]

In 2019, the National Association of Attorneys General looked at several dozen Supreme Court briefs and selected three as meriting the moniker of “best brief.”[148] Rather than provide a rote roadmap introduction, each winning brief set forth an introduction that made clear where the writer stands by including point of view, frame, and perspective.

The first example is the brief of the lawyers for the Commonwealth of Virginia, which set forth their introduction in Virginia House of Delegates v. Bethune-Hill[149] this way:

Two points of black-letter law and a straightforward application of this Court’s precedent resolve this case.

The black-letter law is:

Standing rules apply only to parties playing offense, not defense; and

As the party playing offense, an appellant must have “standing to appeal.” Wittman v. Personhuballah, 136 S. Ct. 1732, 1735 (2016).

The only appellants here are the lower chamber of Virginia’s bicameral state legislature and its speaker (together, the House). The House does not represent the Commonwealth of Virginia, and a component of state government has no standing to appeal that is separate from the State of which it is a part.[150]

The point of view seeks application of “black-letter law.” And the authors frame the case as a “straightforward application of this Court’s precedent,” and their perspective is implied in the brusque tone used. They seem to say, “Why are we even here?”

The next example is the brief of the State of Missouri in Bucklew v. Precythe,[151] a case challenging the state’s method of execution as violating the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment. The authors of the State’s brief started with this:

Justice is long overdue for Russell Bucklew. Over 22 years ago, in a vicious crime spree, Bucklew committed murder, attempted murder, kidnapping, rape, escape from jail, and assault. He was convicted and sentenced to death. He now seeks an effective exemption to the death penalty through an as-applied challenge to Missouri’s method of execution.[152]

“Justice is long overdue” for whom? For the State of Missouri. The point of view is that of the justice seeker. The defendant, by contrast, “seeks an effective exemption to the death penalty through an as-applied challenge to Missouri’s method of execution.” Sounds feeble compared to the lofty value aspiration of “justice.” This contrast sets the frame of what the case is about. And for perspective, the author’s “take” on this case clearly opposes the defendant who “committed murder, attempted murder, kidnapping, escape from jail, and assault,” yet seeks exemption from justice. The frame summarizes justice herself.

Both these briefs offer examples of how the Big Picture, “where you stand,” with the elements of point of view, frame, and perspective, serve as a compelling alternative example to the roadmap introduction. In heeding Adams’s advice to photographers, legal writers can capture their readers’ attention and draw them into the work without wasting their time or condescending to them with a roadmap for a legal document, the contents of which they are almost certainly already familiar.[153]

As pointed out above, Chief Justice Roberts recommends that legal writers “give them an idea of, not a road map, not a summary, but your main argument.”[154] Who knows if the Chief Justice has a Nikon, but whether he knows it or not, he appears to be an Ansel Adams enthusiast.

C. Conclusions: Express What You Feel

1. The Traditional Conclusion and Legal Writing

The typical recommended conclusion for persuasive writings is the one that “tells the reader what you told him”—basically a quick, often repetitive, summary. This applies in high school writing and college writing,[155] where the conclusion should end with a restatement of the thesis statement that “give[s] readers satisfying closure.”[156] College writers are instructed to use the conclusion to “summarize[] or restate[] the main idea.”[157] Middle school writers, too.[158]

Lawyers are also taught to adhere to the “tell 'em of what you told them” method of conclusion writing. More than a century ago, the treatise Legal Reasoning and Briefing provided the following advice on how to draft a conclusion: “The conclusion . . . need be little more than a summary of the main steps in the argument, together, in some very extended discussions, with a review of the main points supporting them.”[159]

Judge Re, in his treatise on brief writing, states that the conclusion is a “summarization of the key facts and principle of law [so that] [t]he court would then close the brief remembering the final summary of the case as well as the relief requested.”[160] Professors Mary-Beth Moylan and Stephanie J. Thompson, in the coursebook Global Lawyering Skills, state that “[i]n the final conclusion, it is the advocate’s job to restate persuasively the conclusion forecast in your introductory paragraph.”[161] This concept of restatement is wrong.

Before explaining why this is so, we note that in some circumstances, court rules are clear that a conclusion must only “stat[e] the precise relief sought.”[162] Where that is the rule, it must be followed, and the next sections of this article become more abstract than advisory.

2. In Most Persuasive Legal Documents, a Traditional Conclusion with Summary Serves Little Purpose as Sophisticated Readers Have Already Read the Argument and Either Are Convinced or Not

When rules do not handcuff the legal writer to a short conclusion that states only the specific relief requested, choice presents itself. The typical conclusion that summarizes what has been argued is a poor choice. Dealing with a sophisticated reader, whose job is to read the argument, restating what was just read is patronizing. For all the same reasons as a “tell 'em what you are going to tell 'em” introduction is a waste of readers’ time, so too is a “tell 'em what you told 'em” conclusion.[163]

And to not waste your time, I move on to how Ansel Adams’s principle of showing how you (the writer) feel about the case is a good choice for a conclusion to a persuasive legal document.

3. Adams’s Photographs Evince His Feelings Toward the Subject, and in Doing So Influence the Viewer to Feel Likewise

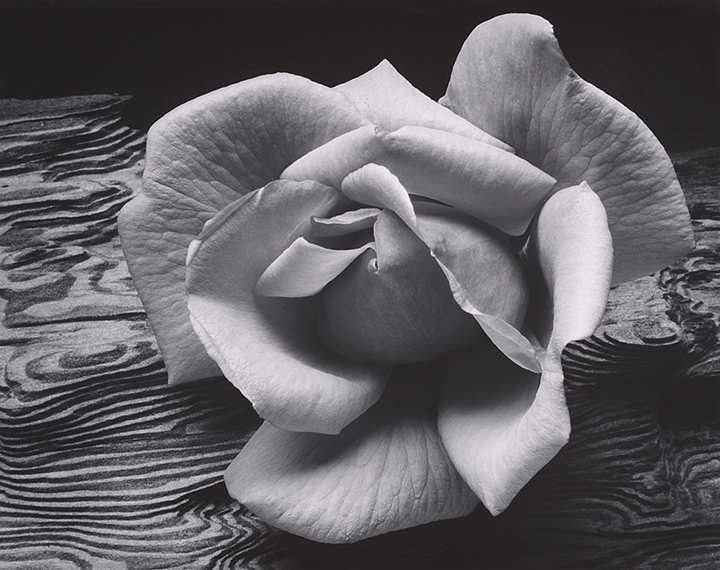

Rose and Driftwood [164] is an anomaly for Adams. It is essentially a still life, a work of art that depicts an inanimate object—usually an ordinary one.[165] Almost all of Adams’s photographs depict landscapes or occasionally people; they are not still life works.

In its simplicity, and in its “stillness,” Rose and Driftwood exemplifies Adams’s advice to “fully express[] what one feels, in the deepest sense, about what is being photographed.” Looking at it, one feels grace, elegance, simple beauty. Adams explained how emotionally he came to make a photograph of something so ordinary.

We observe few objects really closely. As we walk on the earth, we observe the external events at two or three arms’ lengths. If we ride a horse or drive in an automobile, we are further separated from the immediate surround. We see and photograph “scenery”; our vast world is inadequately described as the “landscape.” The most intimate object perceived daily is usually the printed page. The small and common place are rarely explored.[166]

In the ordinary, there is feeling, and feeling motivates; feeling persuades. Like the simple Rose and Driftwood, feeling often finds its proper home in a legal writing document conclusion.

4. Why Pathos in a Conclusion Improves a Piece of Persuasive Writing

Choice is the essence of composition. Adams’s principle is that “[a] great photograph is one that fully expresses what one feels, in the deepest sense, about what is being photographed . . .” In that observation lies advice on how to conclude a persuasive legal document: capture how one feels. In other words, evoke pathos.

Pathos packs power. While blatant pathos may backfire as being overtly manipulative,[167] pathos plays an important role in all persuasive writing, including legal writing. While cautioning against over-reliance, Professor Kenneth D. Chestek notes that a brief writer “who overlooks the emotional appeal of her case does so at her client’s great peril.”[168] Similarly, Professors Helene F. Shapo, Marilyn R. Walter, and Elizabeth Fajans endorse restrained use of pathos. Employing pathos “can evoke sympathy for your client’s suffering, anger at the defendant’s cruelty, or respect for fairness and justice.”[169]

The effective use of pathos in legal writing in the form of narrative,[170] metaphor,[171] word choice,[172] and even writing with rhythm, tone, and flow[173] are explored elsewhere. Below, this article focuses on the conclusion and only the conclusion. And while the following discussion offers a suggestion on how to deploy pathos in a conclusion, there is no suggestion that the other tools—ethos and logos—should be ignored. Rather, the suggestion here is merely one of the tools that a writer should consider. Like a carpenter at her workbench, there are many tools, and which one to use when is the essence of her trade.

Aristotle taught three main tools to legal argument—ethos, pathos, and logos.[174] In other words, credibility of the writer, emotion of the audience, and the logic of the argument itself.[175] Traditionally, lawyers rely on logos as the primary arrow in their argument quiver, but ethos and pathos cannot be left out.[176] Professor Michael Smith explains that in legal writing, there is an inverse relationship between pathos and logos—“the stronger one’s logos, the less important one’s pathos.”[177] This relationship between pathos and logos directly impacts the legal writer’s choices in general and is central to the use of Adams’s second principle of composition: “A great photograph is one that fully expresses what one feels, in the deepest sense, about what is being photographed . . .” Here’s why.

When the law is clear and compelling based on binding authority (logos), decision-makers will almost always follow it.[178] They have little choice. But where the law is unclear, the decision-maker is forced to render a decision they think is “right.” But what is “right” is often a function of values, and values are influenced by pathos-based appeals.[179] Logos makes the reader think the writer is right; pathos makes the reader feel the writer is right.

Thus, faced with the task of getting the reader to agree, lawyers can rely either on justifying arguments (based on how the law requires a result) or motivating arguments (based on values). These motivating arguments “make a judge want to rule in favor of your client,” and they are pathos-based.[180] Motivating arguments take advantage of the unique relationship between reader and writer: that we lawyer/writers “have ‘the soul of the reader’ in our hands during the fleeting time that the judge will be reading our briefs.”[181] Motivating arguments should be at the heart of a persuasive legal text when, as is often the case, the law is unclear.[182]

Classically, logos-based appeals are in the statement of fact and argument sections, and pathos-based appeals are in the conclusion section.[183] That advice is echoed by modern scholars:

A pathos-based argument can be effective [in the conclusion] when appropriate to evoke the sympathy, prejudice, feelings, or shared values of the audience. The conclusion also includes a clear, concise final review of the essential facts and central arguments of the case, as well as a restatement of the theme.[184]

Pathos has been rightly used in the conclusion sections of appellate briefs, for example. In his recent book, Judge Robert E. Bacharach argues that a conclusion should “crystallize what you have developed by ending strongly.”[185] Judge Bacharach provides an example from the defendant’s brief in Ohio v. Clark[186] that “fully expresses what one feels, in the deepest sense.”[187] At issue in the case was the admissibility of a child’s statement to his teachers. The brief, written by Stanford Law professor Jeffrey L. Fisher, concluded this way:

As hard as child abuse sometimes is to prove, it has been recognized for centuries that such a criminal charge is even “harder to be defended by the party accused, though innocent.” Indeed, due to the “heinousness of the offence,” there is a special danger that the jury may be “overhastily carried to the conviction” by false or inaccurate accusations. For hundreds of years, the Anglo-American legal system has recognized that the best antidote to this danger is cross-examination—“the greatest engine ever invented for the discovery of truth.” This Court should turn away the State’s request to systematically dispense with that protection where it is most needed.[188]

This powerful conclusion offers flowing prose that harnesses and deploys pathos by focusing the justices on dedication to truth finding.

Legal writing consultant Ross Guberman explains why and how to deploy pathos in the conclusion instead of a summary of what was just argued. You should end your brief with a bit of “heft” and “[i]f you’ve kept your emotions in check throughout your argument, let yourself vent a bit in your conclusion.”[189] He quotes a particularly effective conclusion penned by Nancy Abell, Global Chair of Paul Hastings Employment Law Department. Abell wrote in the conclusion to her brief in Doiwchi v. Princess Cruise Lines:[190]

The trial judge correctly observed: “There’s absolutely no evidence at all that any discrimination was taking place.” Doiwchi herself conceded that even she does not believe that she was let go because she has a learning disability. The record is devoid of substantial evidence of intentional discrimination. So, too, is it devoid of the requisite proof that those accused of failing to accommodate knew that Doiwchi had a covered disability and a disability-caused work-related limitation that required accommodation. Doiwchi never told.[191]

The reader feels no sympathy for Ms. Doiwchi. None.

I offer one final example to bring home the point that pathos has a place in conclusions. A swamp sits in Southern Illinois. Swamps, now called wetlands mostly, are dark and eerie and magical. Such a swamp, currently called the Cache River State Natural Area,[192] was in peril. Farms encroached on the swamp, rendering it smaller and smaller. In the early 1980s, the State of Illinois built a dam to hold the water and keep what remained of the swamp swampy. Farmers wanted the dam torn down and the swamp drained. The State obtained an injunction preventing the removal of the dam, and thus saving the swamp. The farmers, through the local drainage district, appealed.[193]

As a young lawyer in the Illinois Attorney General’s Civil Appeals Division, I represented the Department of Natural Resources. Back then, like now, I was a photographer and a fan of Ansel Adams. I do not recall that when I wrote the appellate brief I was thinking of Adams’s principle of a great photograph as one that “fully expresses what one feels, in the deepest sense” or that such a principle had any unconscious influence on me.

But, yet, in pulling out and dusting off my somewhat yellowed copy of my January 27, 1987, Brief of Plaintiff-Appellee, I find that my conclusion heeds my decades-later advice. I wrote:

The status quo seeks to keep the District from engaging in certain activities that may well doom the finest and one of the last remaining cypress-tupelo swamps. The ecological, scientific and national importance of the Lower Cache River Natural Area cannot be understated. . . . At stake here is the last remnant of a cypress swamp in the State of Illinois. Decisions must not be made lightly. The Drainage District intends to do just that—act with haste and without adequate information. . . . The preliminary injunction [should be affirmed] so that the merits of such can be adjudicated and irreparable damage to a valuable natural landmark and a precious natural resource will not result from a hasty mistake.[194]

“Hasty mistake: could spell ‘doom’” was the pathos-based point the appellate judges read last in my brief, and it was how I felt about the issue. I had been to the swamp to help prepare for the case. I was awed by its beauty and angered by the cavalier attitude of the drainage district that sought to destroy it.

My use of those feelings about the issue through the words in my brief proved effective. The court agreed with me. The three-judge panel affirmed the grant of the preliminary injunction, holding that the “District’s future plans [to tear down the dam], could well result in the drying up of the Swamp with disastrous consequences to the unique plant and animal life.”[195] Today, almost 40 years after I “fully express[ed]” in that brief how I felt about the issue, “in the deepest sense,” the Cache River State Natural Area lives on as “an ecological gem” and is recognized as a “Wetland of International Importance.”[196]

V. Conclusion

Lawyers are artists, legal writing an art.[197] Just as artists like Ansel Adams used the rules of composition as suggestions rather than mandates, so too the use of Adams’s two composition “rules” for lawyers only suggest a tool for legal writers. In his 1954 ABA Journal article, New York lawyer and an early advocate for improving legal writing Eugene Gerhart[198] wrote:

Writing is like painting a picture [making a photograph] or planning a battle. The techniques and the strategy will be governed by the facts and circumstances of each case. The best writers, like the best artists and the best generals, will achieve their results without being mastered by the rules.[199]

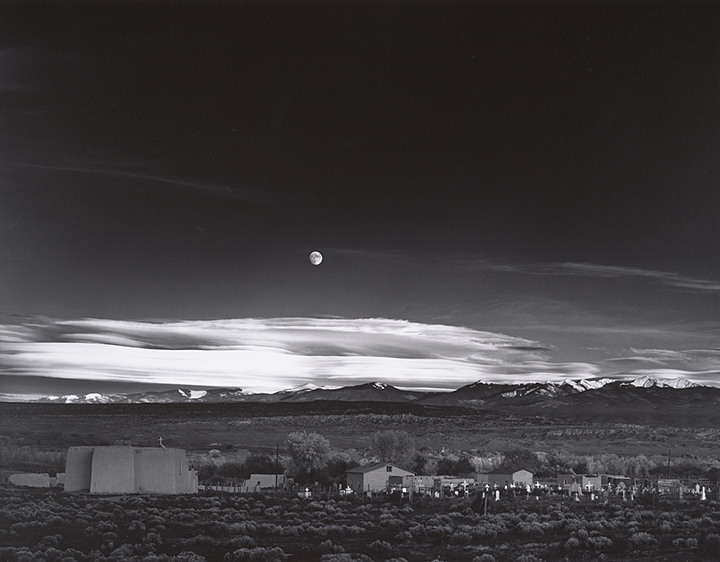

Not being mastered by the rules requires a mastery of the rules—to intentionally know what to use and not use, when, and how. Ansel Adams knew that and applied the rules as fit the circumstances. For example, one of his most famous images—perhaps his most famous—Moonrise Hernandez New Mexico, seemingly avoids all the traditional photo composition principles like the Rule of Thirds, Leading Lines, and others.[200]

But that disregard of the rules does not mean Adams lacked the skill and knowledge of how and when to use the rules. Avoidance does not mean that he ignored the fundamental principles of (1) knowing where to stand, and (2) fully expressing his feeling about the subject—the two principles set forth in this article. Rather, Adams’s most famous image embraced these two principles.

First, as to where to stand, Adams was struck by the scene as he drove down the desert highway late in the afternoon. Adams explained how he knew where to stand in his book, Examples: The Making of 40 Photographs: “We were sailing southward along the highway not far from Espanola when I glanced to the left and saw an extraordinary situation—an inevitable photograph! I almost ditched the car and rushed to set up my 8×10 camera.”[201] And he made the image. Knowing where to stand was the first part of the famous image and should be the first part of any persuasive legal writing.

Second, as to expressing how he felt about the subject matter of this image, the Norton Simon Museum’s discussion of Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico notes that in the image, “Adams captures the intense, emotional response he experienced watching the rising moon illuminate the small town of Hernandez, New Mexico . . . in which an otherwise ordinary evening in a seemingly deserted city has been transformed into a powerful, mystical moment in time.”[202] How Adams felt about the subject transfers to the viewer as the lasting take-away from the viewing experience. So, too, the conclusion of persuasive legal writing should express how the author feels so that such feeling transfers to the reader inching him or her towards agreement with the argument.

Ultimately, lawyers should master the writing equivalent of Ansel Adams’s two principles of photo composition—know where you stand for an introduction and show how you feel in a conclusion. To be sure, as writers we have choices and we can choose to employ these two principles never, sometimes, or often.

I choose to employ these principles often as I have done in this article. I respectfully encourage others to also consider and employ them.

For example, fiction writing (Pam Jenoff, The Self-Assessed Writer: Harnessing Fiction Writing Processes to Understand Ourselves as Legal Writers and Maximize Legal Writing Productivity, 10 Legal Comm. & Rhetoric 187 (2013)); screenwriting (Teresa M. Bruce, The Architecture of Drama: How Lawyers Can Use Screenwriting Techniques to Tell More Compelling Stories, 23 Legal Writing 47 (2019)), and even nineteenth century horror writing (Julie A. Oseid, What Lawyers Can Learn from Edgar Allan Poe, 15 Legal Comm. & Rhetoric 233 (2018)).

Quoted in James P. Ronda, Visions of the Tallgrass: Prairie Photographs by Harvey Payne xii (2013).

Quoted in Encyclopedia of Twentieth-Century Photography 11 (Lynne Warren ed., 2006).

James Alinder & Nicolai Cikovksy, Jr., Ansel Adams: Classic Images, The Museum Set 20 (1985) [hereinafter Classic Images].

John Szarkowski, Introduction, in Ansel Adams, The Portfolios of Ansel Adams vii (1981); see generally William Turnage, Ansel Adams, Photographer—Bio, The Ansel Adams Gallery (July 5, 2023) https://www.anseladams.com/ansel-adams-bio/ [https://perma.cc/9T5B-KCXS].

Classic Images, supra note 4, at 20.

See Jimmy Carter, Nat’l Portrait Gallery, https://americaspresidents.si.edu/object/npg_NPG.80.305 [https://perma.cc/WNM4-4HCE] (last visited Jan. 7, 2024).

Two notable exhibitions were Ansel Adams in Our Time, Museum of Fine Art, Boston (Dec. 13, 2018–Feb. 24, 2019), and Ansel Adams: Pure Photography, New Mexico Museum of Art (Jan. 29, 2022–May 22, 2022). For a comprehensive list of museum exhibitions featuring Ansel Adams, see Exhibitions: Ansel Adams, Mutual Art, https://www.mutualart.com/Artist/Ansel-Adams/3F5A76943B758985/Exhibitions [https://perma.cc/6KWS-8EKP] (last visited Jan. 7, 2024).

Books after his death include Rebecca A. Senf, Making A Photographer: The Early Work of Ansel Adams (2020); Ansel Adams, Ansel Adams in the National Parks: Photographs from America’s Wild Places (Andrea G. Stillman ed., 2010); Ansel Adams & Pete Souza, Ansel Adams’ Yosemite: The Special Edition Prints (2019); and many others.

Steven Brower, The Visual Art and Design of Famous Writers, Print: Design Books (June 25, 2012), https://www.printmag.com/design-books/the-visual-art-and-design-of-famous-writers/ [https://perma.cc/U3HU-85DR].

Christopher Shultz, Authorial Artists: 5 Painters Who Also Wrote, LitReactor (June 26, 2013), https://zerocool.litreactor.com/columns/authorial-artists-5-painters-who-also-wrote [https://perma.cc/9QQX-J3WG].

See Jeanne C. Reesman, Sara S. Hodson & Philip Adam, Jack London, Photographer (2010).

Eudora Welty & William Maxwell, One Time, One Place: Mississippi in the Depression: A Snapshot Album (1996); Eudora Welty, Reynolds Price & Natasha Trethewey, Eudora Welty: Photographs (2019).

Donald Friedman, The Writer’s Brush: Paintings, Drawings, & Sculpture by Writers, XIX (quoting W.B. Yeats, Art and Ideas, in The Collected Works of W.B. Yeats Vol. 4, The Early Years 255 (George Bornstein & Richard J. Finneran eds., 2007)).

David Prakel, Basics Photography 01: Composition 13 (2d ed. 2020); Bruce Barnbaum, The Art of Photography: An Approach to Personal Expression 1 (1st ed. 2011) [hereinafter The Art of Photography].

Mary-Beth Moylan & Adrienne L. Brungess, Persuasive Legal Writing, in Global Lawyering Skills 129 (Mary-Beth Moylan & Stephanie J. Thompson eds., 1st ed. 2013).

Quoted in Eric H. Hobson, Seeing Writing in a Visual World, in ARTiculating: Teaching Writing in a Visual World 1 (Pamela B. Childers, Eric Hobson & Joan A. Mullin eds., 2013).

Stephen Walton, Understanding Your Audience as a Photographer, iPhotography Blog (Nov. 30, 2022), https://www.iphotography.com/blog/understanding-your-audience-as-a-photographer/#:~:text=It’s important to know this,your beliefs %26 style)%20accordingly [https://perma.cc/X65D-K8NG].

Wayne Schiess, Legal Writing Is Not What It Should Be, 37 S.U. L. Rev. 1, 2 (2009).

Composition, Online Etymology Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/word/composition#etymonline_v_28495 [https://perma.cc/4DKZ-545Z] (last updated Feb. 17, 2018).

Paul Norman, reading as performance/reading as composition, J. Artistic Rsch. 20 (2020), https://www.jar-online.net/en/exposition/abstract/click-more-information-reading-performance-reading-composition [https://perma.cc/RFV2-9DR2] (sub. req.).

Romanas Naryškin, The Art of Composing Photos, Photography Life (Jan. 20, 2022), https://photographylife.com/art-of-composing-photos, [https://perma.cc/C2H9-BWNV].

A simple definition of “composition” is offered by London’s Tate Modern Museum: “Composition is the arrangement of elements within a work of art.” Art Term: Composition, Tate, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/c/composition [https://perma.cc/L2M8-P9KP] (last visited Jan. 7, 2024).

See generally Klaus R. Scherer & Marcel R. Zentner, Emotional Effects of Music: Production Rules, in Music & Emotion: Theory & Research 361–87 (Patrik N. Juslin & John A. Sloboda eds., 2001).

John Suler & Richard D. Zakia, Perception and Imaging; Photography as a Way of Seeing 124 (5th ed. 2018).

See The Writing Center, What is Rhetoric, George Mason Univ. Writing Ctr., https://writingcenter.gmu.edu/guides/rhetoric [https://perma.cc/34QE-QEF2] (last visited Jan. 7, 2024) (“Rhetoric is the study of how writers use language to influence an audience.”); see also Janine Butler & Stacy Bick, Audience Awareness & Access: The Design of Sound & Captions as Valuable Composition Practices, 74(3) College Composition & Commc’n 416 (2023).

Adorama, 15 Photo Composition Techniques to Improve Your Photos, Adorama 42 West, https://www.adorama.com/alc/basic-photography-composition-techniques [https://perma.cc/9FR4-62KZ] (last updated May 16, 2022) (“The main purpose of composition is to influence viewing behavior. This entails understanding the principles of composition in photography and knowing how to lead your viewer’s eye to your subject or whatever focal point you want them to look at.”).

The Art of Photography, supra note 15, at 17.

Id.

Moylan & Brungess, supra note 16, at 129.

Many sources refer to “photographic composition,” while seemingly just as many refer to “photography composition.” For purposes of this article, I will compromise and call the practice “photo composition.”

Catherine J. Cameron & Lance N. Long, The Science Behind the Art of Legal Writing 3 (2015) (“There are more than 150 books on legal writing in the known universe.”).

Classic Images, supra note 4, at 9.

The Art of Photography, supra note 15, at 328–30.

See generally Donald Friedman, The Writer’s Brush: Paintings, Drawings, & Sculpture by Writers (2007).

Catherine Golden, Composition: Writing and the Visual Arts, 20(3) J. Aesthetic Educ. 59 (1986) (discussing how understanding the process of painting can help writers with the process of revision); see generally Princeton Univ. Press, Overview to Leonard Barkin, Mute Poetry, Speaking Pictures (quoting Plutarch: “painting is mute poetry, poetry a speaking picture”; and quoting Horace: “as a picture, so a poem”), https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691141831/mute-poetry-speaking-pictures [https://perma.cc/K2B4-UZVG] (last visited Jan. 7, 2024).

Ezra Pound, Affirmations, The New Age: A Weekly Review of Politics, Literature, and the Arts 349 (Jan. 28, 1915), https://repository.library.brown.edu/studio/item/bdr:444174/PDF/[https://perma.cc/A3N5 -XKEM].

Randy Fox, Visual Rhetoric: An Introduction for Students of Visual Communication, AIGA Colorado (Jan. 9, 2013), https://colorado.aiga.org/2013/01/visual-rhetoric-an-introduction-for-students-of-visual-communication/ [https://perma.cc/QK4G-3RAN] (citing Purdue Online Writing Lab (OWL), http://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/691/01/ [https://perma.cc/U94E-4UAZ]).

Id.

Vincent Miholic, Photography: A Writer’s Tool for Think, Rendering, and Revising, 29 J. Coll. Reading & Learning 21, 22 (1998).

Moylan & Brungess, supra note 16, at 1.

Id. (citing Robert B. Shuman & Denny Wolfe, Teaching English Through the Arts (1990)).

See Barbara P. Blumenfeld, A Photographer’s Guide to Legal Writing, 4 Persps.: Teaching Legal Rsch. & Writing 41 (1996).

Email from Barbara Blumenfeld to Bret Rappaport, May 17, 2022 (on file with Bret Rappaport).

Adams is quoted as stating the truism this way: “You don’t take a photograph, you make it.” See Jordan Anthony, Photography Quotes—A Selection of the Best Quotes from Photographers, Art in Context, https://artincontext.org/photography-quotes [https://perma.cc/A7QP-ZKKU] (last updated Sept. 5, 2023).

Naryškin, supra note 22; see also id. (“Composition is a way of guiding the viewer’s eye towards the most important elements of your work, sometimes—in a very specific order.”).

Rhetoric, according to Aristotle, is “the faculty of.” Scholarly Definitions of Rhetoric, American Rhetoric, https://www.americanrhetoric.com/rhetoricdefinitions.htm [https://perma.cc/KAF3-AMHZ] (last visited Jan. 7, 2024).

Tom Grill & Mark Scanlon, Photographic Composition: Guidelines for Total Image Control Through Effective Design 14 (1990).

Id.

Sonja K. Foss, Ambiguity as Persuasion: The Vietnam Veterans Memorial 34(3) Commc’n Q. 326, 329 (1986) (“Visual works of art, then, may be considered rhetoric in that they produce effects and are intentional and purposive objects.”).

See Composition (visual arts), Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Composition [https://perma.cc/K9R6-QC28] (visual arts) (last modified Dec. 14, 2023).

Nicholas Mitchell, Learning Composition: The Rule of Thirds, Photodoto, https://photodoto.com/rule-of-thirds/#:~:text=The theory of the rule,points where elements can land [https://perma.cc/QH7E-27WJ] (last visited Jan. 7, 2024).

See Alex Wrigley, Leading Lines—How Can They Improve Your Photo Composition?, Click and Learn Photography, https://www.clickandlearnphotography.com/how-to-use-leading-lines-to-improve-your-photography-composition/ [https://perma.cc/U84L-ANZP] (last visited Jan. 7, 2024).

James Maher, How to Correctly Use Negative Space in Photography, Expert Photography, https://expertphotography.com/negative-space-photography/#:~:text=A negative space image occurs,your attention at first glance [https://perma.cc/QJT8-2EAW] (last updated Dec. 30, 2023).

See Adorama, What Is Balance in Photography?, Adorama 42West (Mar. 8, 2022), https://www.adorama.com/alc/what-is-balance-in-photography. The list of texts in notes 52–55 is not exhaustive. In addition to Grill & Scanlon, supra note 48, other excellent books on photo composition include Michael Freeman, the Photographer’s Eye Digitally Remastered 10th Anniversary Edition: Composition & Design for Better Digital Photos (10 ed. 2017) [hereinafter The Photographer’s Eye], and The Art of Photography, supra note 15.

Quoted in Ansel Adams & Robert Baker, The Camera (The New Ansel Adams Photography Series, Book 1) X (1980).

The Art of Photography, supra note 15, at 17.

The Photographer’s Eye, supra note 55, at 60.

The Art of Photography, supra note 15, at 17. Incidentally, about a mile down the Grand Canyon’s South Kaibab Trail is perched a precipice called “Ooh Ahh Point,” for the moment you come upon it, you say “Ooh ahh.” Having hiked the South Kaibab a couple times, I can personally attest to the “momentary experience” of the view, especially at sunrise. To see a photograph that I composed of the sunrise moment at Ooh Ahh Point, see https://www.tripadvisor.com/Profile/bretandjina/Photo/413130952?tab=photos [https://perma.cc/82BR-X6U6] (last visited Jan. 7, 2024).

Yellowlees Douglas, The Reader’s Brain: How Neuroscience Can Make You a Better Writer 148–54 (2015).

Id. (While the author offers three evidence-based theories of how this occurred, for purposes of this paper, it is the fact of interconnectedness that matters, not how it evolved to be so.)

Id. at 152–53.

Id. at 33–35.

Grill & Scanlon, supra note 48.

Jenoff, supra note 1, at 190.

See generally Schiess, supra note 19, at 2–22 (surveying potential causes); Susan H. Kosse & David T. Ritchie, How Judges, Practitioners, and Legal Writing Teachers Assess the Writing Skills of New Law Graduates: A Comparative Study, 53 J. Legal Educ. 80, 85–86 (2003).

See, e.g., Sambrano v. Mabus, 663 F.3d 879 (7th Cir. 2011) (noting poor writing and calling brief “wretched”); see also Interview, A Conversation with Judge Richard A. Posner, 58 Duke L.J. 1807, 1815 (2009); Heidi K. Brown, Converting Benchslaps to Backstops: Instilling Professional Accountability in New Legal Writers By Teaching and Reinforcing Context, 11 Legal Comm. & Rhetoric 109 (2014); Heidi K. Brown, Breaking Bad Briefs, 41 J. Legal Pro. 259 (2017) (following up three years after the publication of her earlier article finding that the problems persisted); Kathleen Elliot Vinson, Improving Legal Writing: A Life-Long Process and Continuing Professional Challenge, 21 Touro L. Rev. 507 (2005).

Schiess, supra note 19 (listing various sources of criticism).

Douglas E. Abrams, What Great Writers Can Teach Lawyers and Judges: Precise, Concise, Simple and Clear, 52 N.H. Bar J. 6 (2011); see generally Bryan A. Garner, The Winning Brief 221–96 (3d ed. 2014); Antonio Gidi & Henry Weihofen, Legal Writing Style 9–154 (3d ed. 2018).

Mark Osbeck, What is “Good Legal Writing” and Why Does it Matter?, 4 Drexel L. Rev. 417, 440 (2012) (“Good writing, as opposed to merely competent writing, also engages the reader.”).

Jennifer Murphy Romig, Legal Blogging and the Rhetorical Genre of Public Legal Writing, 12 Legal Comm. & Rhetoric 29 (2015).

Ann Nowak, The Struggle with Basic Writing Skills, 25 Legal Writing 117 (2021).

See Urban A. Lavery, The Language of the Law: Defects in the Written Style of Lawyers, Some Illustrations, the Reasons Therefore, and Certain Suggestions as to Improvement, 7 A.B.A. J. 277 (1921); see also Steven Stark, Why Lawyers Can’t Write, 97 Harv. L. Rev. 1389 (1984).

Michael A. Blasie, The Rise of Plain Language Laws, 76 U. Mia. L. Rev. 447, 457 nn.60–66 (2022).

Amy Bitterman, In the Beginning: The Art of Crafting Preliminary Statements, 45 Seton Hall L. Rev. 1009 (2015) (citing Kathryn M. Stanchi, The Power of Priming in Legal Advocacy: Using the Science of First Impressions to Persuade Readers, 89 Or. L. Rev. 305, 307 (2010)); see also Robert E. Shapiro, First Impressions: Writing Your Brief’s Introduction, 47 Litig. 17, 18 (2020).

See How to Write a Conclusion for an Argumentative Essay: All Tips, PapersOwl, December 30, 2022, https://papersowl.com/blog/

argumentative-essay-conclusion [https://perma.cc/7Y47-GQBL] (“An area often overlooked in essay writing is the conclusion.”); Rebecca W. Berch, Observations from the Legal Writing Institute Conference: Thinking about Writing Introductions, 3 Persps.: Teaching Legal Rsch. & Writing 41, 42 (1995) (most legal writing books devote only a paragraph or two to introductions).Ian Gallacher, Four-Finger Exercises: Practicing the Violin for Legal Writers, 15 Legal Comm. & Rhetoric 216 (2018).

See, e.g., Bitterman, supra note 75, at 1030 (arguing that practitioners should consider using Preliminary Statements that effectively lay out the narrative theme of the case and then summarize a client’s strongest facts and law).

See infra at notes 159–61.

Nancy Sommers, The Call of Research: A Longitudinal View of Writing Development, 60(1) Coll. Composition & Commc’n 152 (2008); see also Mike Waterhouse & Geoff Crook, Management and Business Skills in the Built Environment 38 (2013).

Paul Powell, Getting the Lead out of Leadership, Heartland Church Network, https://www.heartlandchurchnetwork.com/uploads/5/8/1/6/58163279/getting_the_lead_out_of_leadership__updated_.pdf [https://perma.cc/LP54-N746] (last visited Jan. 7, 2024) (“Communicate effectively. Good people will do right if they know what is going on. Leave them in the dark and they become suspicious and hesitant. One sharing is seldom enough—tell them what you are going to tell them then tell them, and then tell them what you told them.”); see also Joe Asher, Y2K: Keep sending that message, 9 ABA Banking J., 59 (Sep. 1999).

For a historical dive into the many sources of this advice, see Tell 'Em What You’re Going To Tell 'Em; Next, Tell 'Em; Next, Tell 'Em What You Told 'Em, Aristotle? Dale Carnegie? J. H. Jowett? Fred E. Marble? Royal Meeker? Henry Koster? Anonymous?, Quote Investigator (Aug. 15, 2017), https://quoteinvestigator.com/2017/08/15/tell-em/#google_vignette [https://perma.cc/M9R8-HQUQ] (determining the most likely original source was an English newspaper in 1908, ascribed to an unidentified preacher, and it circulated in the domain of religious orators during subsequent decades).

Mary R. Power, Academic Writing, in Working Through Communication 70 (1997), https://www.researchgate.net/publication/27828948_Chapter_8_Academic_writing (sub. req.).

See, e.g., Lovett Sch., Middle School Writing Handbook, at 17 (thesis includes three main points), https://www.sausd.us/cms/lib/CA01000471/Centricity/Domain/3647/Middle School Writing Handbook.pdf [https://perma.cc/6GSU-VRVN]; MacKinnon Middle School Writing Handbook at 2 (“three clear subtopics” in the introduction), https://www.wbps.org/cms/lib/NJ01911727/Centricity/Domain/8/MacKinnonSchoolWritingHandbook.pdf [https://perma.cc/6SWG-JUDL].

See, e.g., W.F. West High School’s Writing Style Guide, at 10, https://chehalisschools.org/wfw/wp-content/uploads/sites/15/2015/06/writing_guide.pdf [https://perma.cc/H2F3-YWFZ] (“Roadmap—lists the body paragraph main ideas in one sentence.”); Hartselle High School Writing Guide, First Edition, at 71, https://www.hartselletigers.org/site/handlers/filedownload.ashx?moduleinstanceid=7438&dataid=3090&FileName=Writing%20Guide%20final%20draft.pdf (the introduction presents a roadmap).

Jan Haluska, The Formula Essay Reconsidered, 78(4) Jan. Educ. Digest 25, 25–30 (2012) (discussing the history of five-paragraph theme as a model for middle school and high school writing); Tara Star Johnson, Leigh Thompson, Peter Smagorinsky & Pamela G. Fry, Learning to Teach the Five-Paragraph Theme, 38(2) Rsch. Teaching Eng. 136 (Nov. 2003).

See, e.g., Barry R. Weingast, Caltech Rules for Writing Papers: How to Structure your Paper and Write an Introduction 4 (Nov. 2014), https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311205596_caltech_rules_for_writing_papers_how_to_structure_your_paper_and_write_an_introduction (sub. req.) (“[T]he last paragraph [of your introduction] should always be a roadmap.”).

Annual Reports, Purdue Online Writing Lab (OWL), https://owl.purdue.edu/writinglab/about/writing_lab_annual_reports.html [https://perma.cc/T6FF-AVLT] (last visited Jan. 12, 2024).